The history and evolution of the genre

The act of noticing something, with your eyes or hands or nose, comes naturally to humans. When you start playing a video game, it’s one of the first things you do: notice things. What buttons do I press? Which way do I go? What items can I grab? Hidden object games focus singularly on this one idea — the gameplay of searching — to create compelling environments, to tell stories, and to build out worlds.

You could argue that there are elements of hidden object games in most video games. The inherent mechanic is in reacting to things hidden in an environment, whether that’s a patterned ledge, as an environmental clue, or an object literally hidden within a space. Going even further, people have been playing hidden object games for hundreds of years — seeking out hidden objects in illustrations or simply spotting objects in the world, à la I-Spy.

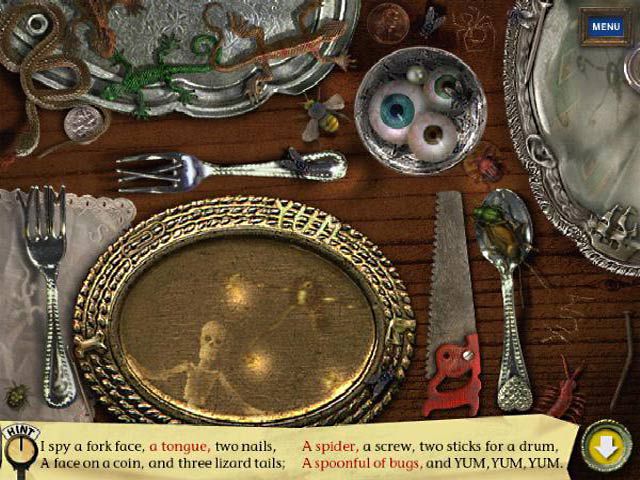

The earliest hidden object games were, of course, ones that could be played without any equipment. Illustrators began adapting puzzles into books, magazines, and newspapers. Think Highlights magazine or I-Spy books, which were later adapted into virtual iterations that worked largely the same way, just with digital motion. I-Spy, for its part, has a series of hidden object video games that go back to 1999, published by Scholastic, like I-Spy Spooky Mansion. It’s about as simple as these games come, with a narrator reading out what they’ve “spied” once the player clicks on an item. Typically, the object will wiggle a bit — or trigger some other simple animation — before the player moves on.

I-Spy Spooky MansionImage: Scholastic Corportion

The core mechanic of hidden object games spans well beyond the video game industry, despite the genre itself remaining in the industry’s margins. A so-called casual genre, hidden object games are played enthusiastically and widely, but largely dismissed as fluff — the same way romance novels are perceived. Hidden object games, some of which center on romance and gothic storytelling, have faced the same fate of those very books, deemed inconsequential or unworthy of analysis and enjoyment.

Some indie games have appeared over the past few years with a re-branding of the genre; a few studios refuse to call their games hidden object games, worried about association with the others, instead focusing on the act of searching. Games like Hidden Folks, Wind Peaks, and even Toem are reimagining the genre as something different. Author and University of Georgia professor Shira Chess, who wrote the feminist video game theory book Ready Player 2, recognized the complexity of these hidden object games in a 2014 paper called Uncanny Gaming: The Ravenhearst video games and gothic appropriation. Chess saw how certain hidden object games ”both reinforce[d] and complicate[d] the expectations of women gamers,” but continued in the genre’s legacy of “push[ing] against some traditional conventions […], illustrating how digital spaces have begun to rewrite traditional narrative conventions.”

Searching the past

“Hidden object games were one of the first genres that were really meant for an assumed feminine audience,” Chess told Viaggio247. The “assumed” here is important, Chess said.

Hidden object games, like the works of Jane Jensen, who famously reimagined popular novels into adventure hidden object games, have historically featured lots of female protagonists. This, paired with the organizational nature of these games, led to the genre being driven toward a perceived female audience — the other. The lack of barriers to entry, whether that’s a device that can play these games or knowledge of the mechanics of play, made for a slower, more approachable game.

One of the real benefits of the genre is that mechanics were able to shift and adjust to allow for different sorts of storytelling: detective crime stories were popular, as were gothic romance and mysteries. Though the gameplay is considered slow, it’s still gameplay used to tell a story.

“I think we’ve only scratched the surface of players that will be interested in this”

“I think the reason hidden object games both get ignored and also stand out among the genre of casuals is that we tend towards thinking about games in terms of speed, in terms of action, in terms of what’s happening on the screen,” Chess said. “Not the action of what’s happening internally with the player.”

In the book Jane Jensen: Gabriel Knight, Adventure Games, Hidden Objects, author and professor Anastasia Salter wrote that hidden object games “started out from scavenger hunt mechanics” that were largely focused around mystery themes. Mystery Case Files: Huntsville (released in 2005), is often cited as the original hidden object game. Regardless, it was a major success for Big Fish, and the start of the genre craze that influenced game design for years to come. In 2007, Mystery Case Files: Ravenhearst, one of many follow-ups in the series, entered a top-selling PC games list in the third top spot during holiday sales season. Reuters reported at the time that the Mystery Case Files franchise appealed largely to women from 35 to 50, making that success even more notable: For an industry that had long pushed women to the margins, the so-called casual gamers were eager to snap up a different sort of game.

Big Fish game production manager Christine Zeigler confirmed to Viaggio247 that Big Fish’s subscribers skew older than the “hardcore” gaming subset. “Looking back, the audience has matured over the years, with 76% of players over the age of 55,” Zeigler said. “Players have consistently been predominantly female, representing 85% of players.” Big Fish declined to provide exact numbers regarding its player base for hidden object games, but Ziegler said the company continues to release new hidden object games every November.

“Lots of our players came from games like Myst, and were looking for point and click adventure-style games that they could dive into and escape in,” Ziegler said. “The interest in bite-sized adventure games has continued over the years.”

June’s JourneyImage: Wooga

In 2013, former Big Fish Studios vice president Patrick Wylie said the Mystery Case Files games garnered “over 100 million downloads” since it was created in 2005. The sheer number of players interested in these games at that time drove companies to invest in this sort of storytelling — often considered an “easy” development path, focusing on still puzzles with little animation. The oversaturation of the genre may have contributed to a maligned perception of hidden object games, once they became bloated full of ads and marketing — something that got more invasive as these games moved into the mobile space.

Regardless, dedicated players continue to flock to these games. Players continue to play Mystery Case Files (and others) on Big Fish, alongside the wildly popular June’s Journey by Wooga and story-driven hidden object games by Polish developer Artifex Mundi.

In recent years, the genre’s evolving.

Hide and seek

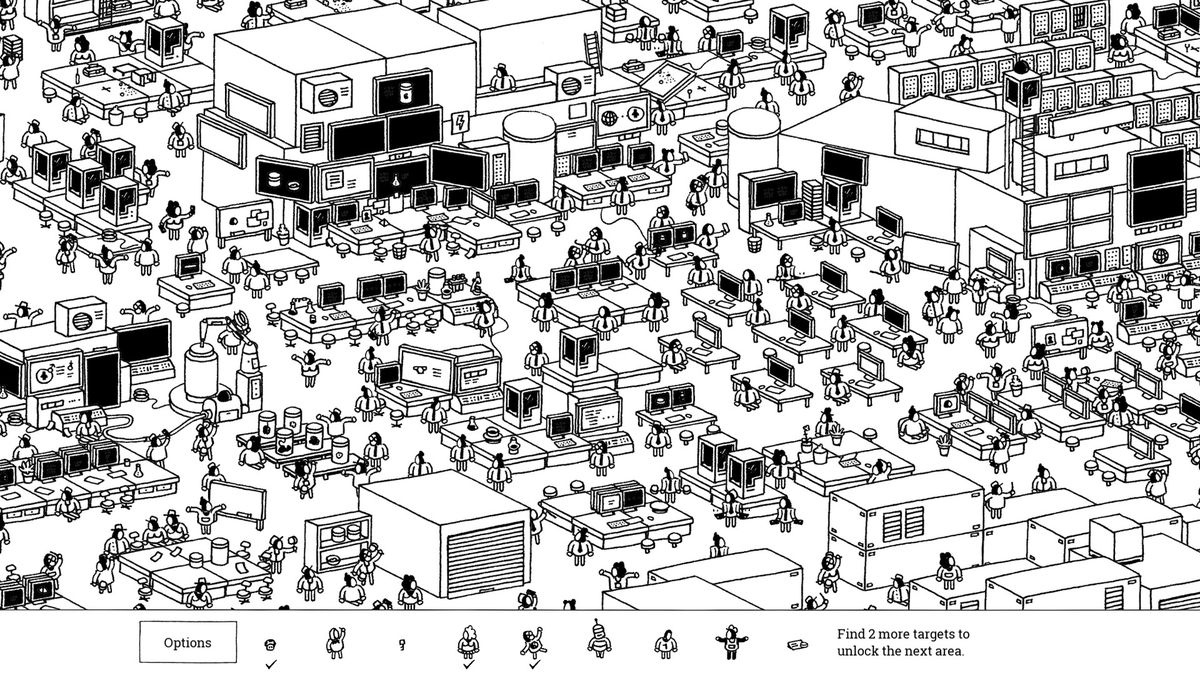

Hidden Folks is not a hidden object game, says developer Adriaan de Jongh. It’s a searching game, one in which players aren’t simply staring at a screen to pull some Where’s Waldo?-esque character from a crowded scene. Sure, there are hidden objects, but they’re less important than the act of searching: unzipping tents, opening windows, shaking trees. Hidden Folks’ hand-drawn worlds, sketched out by illustrator Sylvain Togroeg, are built out with clues designed to facilitate the search — black-and-white bread crumbs masterly placed throughout the spaces.

Hidden FolksImage: Adriaan de Jongh, Sylvain Tegroeg

Though de Jongh hesitates to call Hidden Folks a hidden object game — a genre he says he hates — there is no doubt that the game does share plenty of elements with games of the genre. De Jongh doesn’t want to say it, but to an outsider, it’s clear: Hidden Folks is a hidden object game, even if it’s not intended to mimic the ones that came before it. The game itself is important for the genre, and its popularity and prestige has the potential to illuminate a large wealth of underappreciated games in the genre.

It’s rare for a hidden object game to break into the mainstream, off the front page of Big Fish, where hidden object games always come first. Hidden Folks has been one of the few to shed the stereotype and reach toward an even broader audience. De Jongh told Viaggio247 that Hidden Folks has been played by more than 2 million players. Its popularity has led to a bunch of near-clones, mimicking the game in both its aesthetics and gameplay.

But plenty of games are cleverly iterating on the concept, similarly using the black-and-white palette, like the 100 Hidden series and “interactive city discovery game” Small Life, to make something brand new. Even a board game, MicroMacro: Crime City, is harnessing the genre. Hard Boiled Games’ hidden object board game won a prestigious award — a Spiel des Jahres — this year.

“I think we’ve only scratched the surface of players that will be interested in this,” de Jongh said.

Alongside developers like Wooga and Artifex Mundi creating stories in their popular hidden object games, smaller studios and solo developers are also embracing the nostalgia for the genre in a way that appreciates and evolves the mechanics. Hidden Folks’ breakthrough popularity feels like it’s paved a way for games that embrace the hidden object label to reach mainstream success, breathing new life into the genre that’s ripe for storytelling.

LoftyImage: Devon Wiersma

Solo game developer Devon Wiersma created Lofty, a “dreamlike hidden object puzzler,” in 2017, and is working on a successor now. Unlike traditional hidden object games, Lofty’s worlds spin, letting the player inspect the space from different angles. The player looks for potions hidden in the world, and must interact with and play with the world to find them. Wiersma’s Lofty follow-up, called Lofty Quest, is adding a narrative to the gameplay in a way that hidden object games uniquely allow.

“Often an effective game theme ties into your gameplay and strengthens both in the process, and ‘hidden object’ games prominently feature acts of exploration and searching,” Wiersma told Viaggio247 via email. “Those are themes I’m aiming to incorporate into the narrative. What is a character searching for? What will they discover about themselves or their past? What might they reveal about the world around them?”

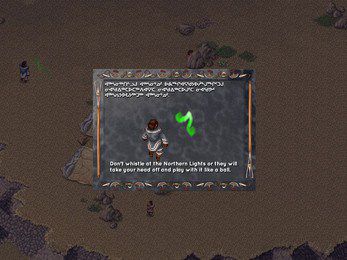

These sorts of narrative themes often help contextualize the act of searching in hidden object games, Wiersma said. It makes a narrative feel natural, and works in all sorts of settings — even in a teaching environment, which is how Pinngauq designer Talia Metuq uses the hidden object format in her Inuit mythology game, Inuit Uppirijatuqangit – ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᑉᐱᕆᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦ, which she told Viaggio247 was designed to teach children about the culture.

Inuit UppirijatuqangitImage: Pinnguaq

Unlike a traditional hidden object game, there isn’t a list of objects to find; instead, it’s up to the player to inspect the detailed pixel art landscapes and click on characters to uncover its secrets. Still, there is a to-do list to help players make sure they don’t miss stories, Inuit Uppirijatuqangit executive producer Ryan Oliver said. “Hidden object [games force] the user to engage in the landscapes,” Oliver said. “It adds a layer of storytelling to the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit that Talia lays out in each story. It serves as a vessel to immerse people in the world Talia designed and provide a simple objective through interaction.”

In a similarly surreal environment, there’s also the mixed reality game HoloVista from developer Aconite.

HoloVista is, as The Verge reported in 2020, “the first mobile game of its kind,” both a hidden object game and a social media simulator controlled by your phone — albeit in an unconventional way. Players physically move their own phones to navigate the mixed reality space, taking pictures of items — like a mermaid tale or starfish in a fantastical mansion — to knock them off a “to find” list. Aconite co-founders Star St.Germain and Nadya Lev do not shy away from the hidden object label; finding objects is, after all, what you do in the game. Like the legacy of the genre before HoloVista, the game uses that mechanic to engage players in story. For HoloVista, that story interrogates our relationship with the technology we use, while using that very same device.

“A new offshoot of hidden object games”

HoloVista benefited from the explicit direction embedded in the genre: Players know exactly what to do, and can easily engage with the game, HoloVista lead designer Scott Jon Siegel told Viaggio247.

“I think it speaks volumes to the potential for hidden object as a genre,” Siegal said. “By definition it’s a style of gameplay that asks players not to just look at a scene or a place, but to really see it. It feels like a very mindful, meditative sort of play. I’ve learned through years of therapy about the calming power of observing your surroundings, and to notice and describe the things you see. Applying the same idea to virtual spaces can feel centering in that same way, even if you find yourself centered in an entirely different world.”

When hidden object games shed the stigma of “genre,” they’re able to immerse players in worlds in ways that are unhindered by skill-based mechanics and complicated controls. The so-called casual nature of these games is why hidden object games get unfairly maligned at times, which is also likely due in part to popularity among women and other marginalized players, like seniors, Wiersma said. Years of game culture and marketing history has deemed casual games as less legitimate, “which adds to their perception as ‘other,’” Wiersma said.

HoloVistaImage: AconiteCo

Most developers noted, of course, that that perception is wrong. Wiersma pointed out that legacy hidden object games target legacy players — people who love the franchises and have for years. Indie games, like HoloVista, Hidden Folks, Inuit Uppirijatuqangit, and Lofty are changing that narrative and expanding the definition of a hidden object game.

“It almost feels, to me, like there’s a market for hidden object games in that indie space — where big, older companies aren’t interested in the risk of pushing to expand outside their market, but potential players who aren’t entirely in the casual space may discover it’s an experience they’re interested in after all and just needed it presented in a different form that might appeal to them more,” Wiersma said. “Almost a new offshoot of hidden object games.”