Filmmakers and writers peel the skin off clichés to get to the meat of the genre

The first time you see a slasher movie, you don’t know that the car won’t start. You’re confused when the main character spots a shady figure outside the window, only to discover in a second glance that they’re no longer there. And you, naive little you, are blown away when the killer survives an attack that seemed more fatal than any of the ones he had inflicted on the jock, the nerd, and the mean girl.

Then you see another slasher movie, and then a few more, and then perhaps a hundred more, and you no longer recall a time when those motions felt like fresh inventions. And it’s not just the slashers that rely on these tropes; we’ve all seen a million ghost movies where a figure appears in the background, then — after the lights flash on then off — finds its way directly next to the protagonist. Any monster movie (at least, post Jaws) has the town event that is too important to close down because of a (bear, rabid dog, or even another shark). And you can’t throw a rock in the zombie subgenre without hitting someone who has been bitten but is hiding it from the rest of the group. No matter what your favorite kind of horror movie is, there are a dozen stock moments and narrative beats that appear time and time again. Some recur because they’re unavoidable. Others are just sturdy — if it ain’t broke, horror people don’t fix it. They haven’t for nearly 100 years.

But how do horror tropes work today? How have they evolved? And how do filmmakers use them to their advantage to bring movies closer to that one original feeling of seeing a classic move onscreen for the first time? To size up the tropes, take stock of the stock characters, Viaggio247 asked horror filmmakers, writers, and experts to weigh in on what’s always worked, and what may continue to scare us in the future. —Brian Collins

The horror tropes that always work

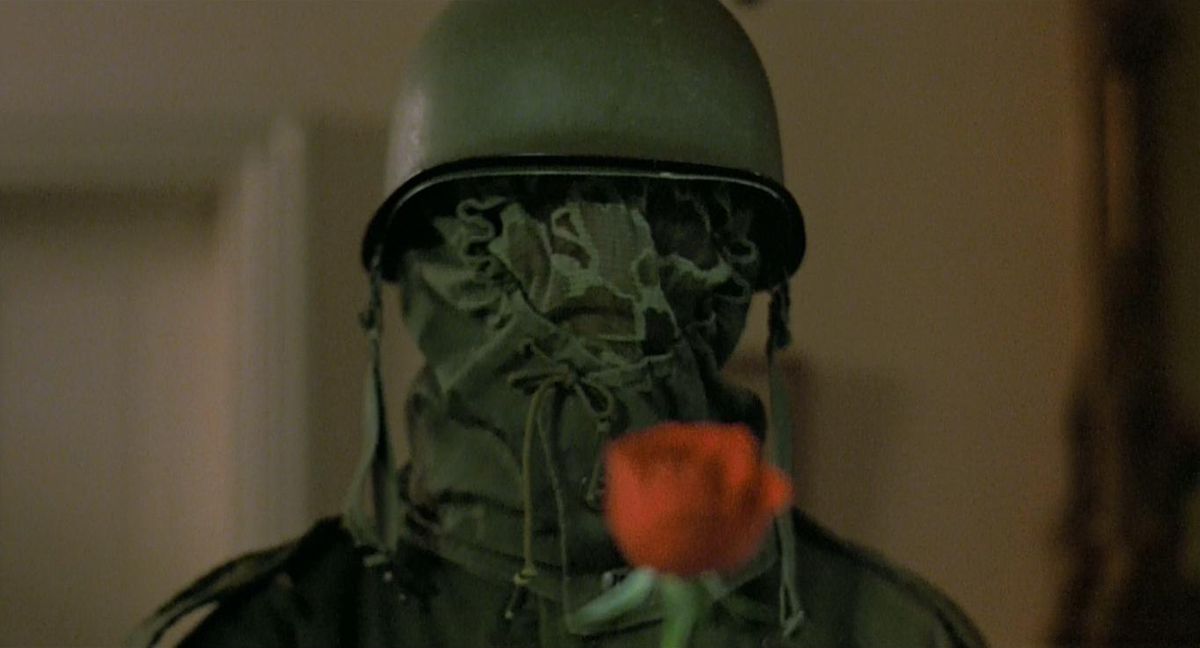

CandymanImage: Tristar Pictures

Amy Searles (co-director, Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies, Los Angeles): I’m sure we’ve all experienced the kind of joke that ebbs and flows upon repetition. Something that’s funny initially can become irritating upon reiteration. But there’s a sweet spot where, if pushed just a little too far, the joke attains a brief period of comedic sublimity, and is funnier than it ever was or had any right to be. In my mind, the horror film equivalent of this rare, heightened state is the mirror scare.

Mirrors are ubiquitous and carry no inherent menace. (Unlike garbage disposals — the Devil’s appliance! — another, similar horror trope I’m fond of.) In a brightly lit bathroom you may be lulled into a false sense of security when a character opens a mirrored cabinet to fetch an aspirin, only to be met by something marvelously grotesque or threatening that triggers the hero and viewer alike the moment the cabinet door is closed.

Todd Farmer (screenwriter Jason X, My Bloody Valentine 3D): A favorite, without question: Cheap-ass jump scares. They get me every time. Remember that supposed car commercial on the internet with car in the distance winding up a curvy valley? Then a zombie screams and faceplants the screen? Shit meself I did. And that was just a silly internet thing. Of course, there’s a great guff between saying “jump scare” and pulling it off because failure to pull it off means a groan from me and the audience. But when you pull off the lawnmower in Sinister … you will never be forgotten.

Axelle Carolyn (director, The Manor, The Haunting of Bly Manor): As a fan of ghost stories and ’70s horror, I’m partial to the emotionally fragile, grieving protagonist who may or may not have just been released from a mental asylum, and finds themself isolated in a countryside house which may or may not be haunted.

Jeffrey Reddick (writer, Final Destination): One of my favorites is how the security goes out at an asylum and a mental patient escapes on the anniversary of the crime they committed. So convenient!

Matt Donato (journalist): “The morgue worker who’s enthusiastically eating while corpses rot on their cold steel tables” gets me every time. Sometimes it’s as simple as sucking on a lollipop, other times the slob gobbles a club sandwich on rye with coleslaw juices oozing everywhere for effect.

Ghoulies 2Image: MGM Home Entertainment

April Wolfe (screenwriter, Black Christmas 2019): Toilet horror has always been a personal favorite as an adult, but as a kid it totally wrecked me. Just the Ghoulies cover alone left me terrified of using the bathroom at night when I was a kid. Friday the 13th: A New Beginning will always have the best toilet kill, however, because nothing tops Demon and his girlfriend Anita singing while he’s on the crapper because of bad enchiladas.

Marc Gottlieb (screenwriter, Aquarium of the Dead): My favorite horror trope is definitely the jumping cat. A feline leaping out of a cupboard, a Dumpster, from the top of a tall cabinet or just about anywhere in a scene that is meant to give the audience a quick, cheap scare. Every time I see it I want to know that cat’s story: What is it doing there? How did it get there?

When it works, it really works, like in Friday the 13th Part II just before Adrienne King realizes she won’t be surviving the wrath of two Voorhees family members, or in Alien when Harry Dean Stanton comes across a scared Jonesy before finding something a lot bigger and more deadly.

Penny Cox (screenwriter, Scream: The TV Series, Legacies): I love any version of the ghost that wants to play. Bounce a ball across the room, roll a toy truck, play a clapping game, talk through a Speak & Spell…

Jared Rivet (writer, Jackals, Are You Afraid of the Dark?): My personal favorite recurring horror is one that’s been around forever but has been showing up in a lot of things lately: In the first act, the lead characters suddenly hit an animal with their car. The roadkill varies from movie to movie, dogs, cats, cows, crows, wolves, coyotes, armadillos, snakes, even, I shit you not, a kangaroo in the case of Long Weekend (1978). But the big winner (loser?) of late seems to be deer. Those suckers just can’t seem to stay out of the path of our unsuspecting, happy-go-lucky horror-movie leads as they innocently cruise ever closer to their doom. It’s a big jolt that no one in the audience sees coming (yeah, right) and it leaves our characters a little shook.

Matt Serafini (author, Rites of Extinction): I’ve got a real soft spot for the Harbinger of Doom. That describes any character who briefly shows up, often drunk, to tell our protagonists they’re about to die. Most notably that’s Crazy Ralph in the first two Friday The 13th movies, but even after he was killed off, the series simply conjured another harbinger to take his place. So right away you got Abel passed out in the middle of the road with an eyeball in his pocket in Friday The 13th Part 3 to continue the tradition in the most nonsensical way imaginable.

Harbingers are not relegated to slasher and survival movies, either. Look at the way the pub scene in An American Werewolf In London turns on a dime, from fish-out-of-water awkwardness to “holy shit these two guys are in danger,” when the entire bar becomes the voice of doom. Or how the main character in the original Invasion Of The Body Snatchers is himself transformed into the hysterical doomer. Just a great, versatile trope.

The tropes that changed with the times

The Prowler (1981)Image: Blue Underground

Brian Collins: What I’ve found with these time-honored story elements is that most of them can be easily adapted to account for changes in technology and the ways we interact with each other today. It used to be easy to get our protagonists lost — they simply had to take a wrong turn or misguided “shortcut” and end up running afoul of whatever mutant family awaited them. Now everyone has GPS in their phones, and so the trope relies on service going out or the map being uncharted. The result may be the same, but getting there is more identifiable to today’s audiences, and we don’t have to lose a perfectly good narrative device simply because it’s outdated. Luckily, some of them are immune from being dated: a cat jumping out of a cupboard in 1980 is no different than a cat jumping out of a cupboard in 2021.

Gottlieb: Dario Argento really doubled down on the trope in Inferno when he hurled something like 11 cats at poor Daria Nicolodi.

Reddick: I think these tropes are the nature of the beast with horror films. If people can call for help the movie would be over right away. Sometimes they’re fun to include because you’re giving the audience a little comfort food. But writers do what they can to adjust to the times. So now instead of “the phone line’s been cut” we get “we can’t get a signal.” That’s progress.

Wolfe: I honestly don’t think filmmakers have used the toilet enough! Maybe it’s because it’s the grossest part of the bathroom, so it’s difficult to make it sexy like the bathtub. But that’s why I appreciate the filmmakers who try. Because sitting on the toilet is the most vulnerable place a human puts themselves multiple times a day. Aronofsky’s Mother! found a way to evoke the toilet moment from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and also make it grosser. All that tissue forming in the bowl, the heart that can’t be flushed. The toilet becomes a surreal portal between the real and the imagined.

And then there’s Julia Ducournau, who just cannot be torn away from her toilet scenes. Titane’s horrific self-abortion scene on the toilet barely even shows the porcelain. It relies almost solely on performance and sound design, and yet it’s some of the best toilet horror I’ve seen in a while.

Serafini: Certainly the last 25 years have become more self-aware. Which means you’ve got The Cabin in the Woods calling blunt attention to tropes with a character actually named Harbinger. More interesting to me, however, is how movies would “twist” this element in the pre-deconstruction era. Take one of the most disturbing slasher movies in existence, 1981’s The Prowler, which uses the sheriff character as a mixture of possible red herring and resident harbinger, delivering a few grave warnings before exiting the movie to go on a fishing trip and then, surprise, surprise, he turns out to be the killer! Making the doomsaying part of the motivation for killing feels like a natural evolution for that trope.

Donato: I feel like food has become infinitely more portable as our lifestyles favor on-the-go urgency, and yet morgue workers still pick such messy meals to savor right around the arrival of another mutilated slasher victim’s body.

Rivet: These days we’ve seen more characters becoming distracted drivers looking for (or at) their cell phones. The trope was definitely around in the pre-cell phone days but now that we have a full generation of distracted drivers, it seems to be a “go-to” trope for horror filmmakers.

Farmer: Certainly for the jump scare the quality has improved exponentially. When I got started, back when we used to walk to school 11 miles in the snow, only Dimension and New Line were making scary movies. That changed after Scream but in today’s world every studio and production company makes horror. Which means demand has increased. Which means the talent pool has evolved. I mean, come on, the guy who wrote Zodiac wrote the new Scream. Chris Rock was in a Saw movie with Sam Jackson. Horror talent has not only evolved but the money and tech that goes into horror has evolved. This leaves no excuse for jump scares not to go to 11.

The timeless tropes

Halloween KillsImage: Universal Pictures

Collins: A filmmaker who opts to avoid typical scares is certainly setting a challenge for themselves, and might be painting themselves into a corner if they can’t rely on the proven formulas and beats of whatever sub-genre they’re tackling. Halloween Kills has been criticized for leaving Laurie on the sidelines and giving her heir apparent Allyson too little to do, so the film essentially lacks a traditional “Final Girl” going through those motions. So is it still a “slasher”? One could argue that by breaking the formula, it ends up denying slasher fans the things they show up for, especially when it’s part of a long running series.

Searles: There is a language to cinema. I know it sounds pretentious, but it’s real. I think many tropes are born of a need to satisfy a familiar and easily understood cinematic syntax. But, as with any language, when one becomes conversant, one of its joys is just how malleable it can be. So while some may utilize clichés for comfort or convenience, in the hands of a thoughtful, playful filmmaker, the rote can be subverted or reinvigorated. Toying with tropes can be a dangerous gambit, however — a lot like making puns. Stick the landing and be met with awe (or “Aww!”). Fumble and suffer the groans.

Serafini: Holistically, I think a lot of this stuff just comes out of the creative process. When you’ve got characters fumbling around in the woods, does it really make the movie any better if the flashlight doesn’t go out? Is it scarier if the call does connect? I’m not saying filmmakers and writers shouldn’t try and think a bit outside the box these days, I’m just saying that sometimes it’s worth asking ourselves what we really want from a horror movie, and if we’re willing to accept a few of these tropes in order to get the story underway.

Carolyn: Part of the reason clichés become clichés in the first place is because they work. You can use them a certain amount of times and get the right reaction. But also, for some darn reason, studios/producers love them. So you might want to avoid them (the clichés … and the producers), but someone in development or post will sneak them back up on you.

Gottlieb: The trope of a car failing to start when the killer is approaching or a victim making a noise that gives their hiding place away are moments that are immediately relatable and, if done well, amp up tension and deliver a great scene. I don’t think clichés themselves are necessarily a bad thing, it’s all about how the filmmaker comes up with their fresh take on portraying any particular cliché.

Wolfe: The common theory for this is that moments that truly scare us become more indelible and etched on the brain. We could forget most of a film over time, but the scenes that scare us will stick in our memories because of hormones and chemicals and the way the brain works. With that in mind, people who’ve seen even a few horror films have already learned these scares. They’ve been primed to expect them. So even the most casual horror fan will be prepared for certain things. I think in filmmaking, you’re always looking for the fastest way to the point of terror, and the fastest method is by getting to that trope to release all those brain chemicals, wiping it to the side, and then offering a new version of it. It doesn’t mean that has to be done. But for mainstream horror, that seems to be the key. Indie and art horror seem to offer more license to buck the tropes, but they’re still there. Everyone uses the toilet!

To trope or not to trope

Friday the 13th Part 2Image: Paramount Pictures

Collins: With so many horror movies being made now thanks to the glut of streaming services needing content — and horror has always been a safer and cheaper option than any other genre — it’s becoming harder to surprise audiences. You also have to set yourself apart from the healthy competition, which means luring in the viewers with the promise of something they know they’ll enjoy from experience, but also make it stand out from those things by subverting as many expectations as you can without actively turning off those viewers who may want things to be kept simple and “comforting”, especially around this time of the year. Finding the fine line between tradition and innovation is something every genre filmmaker has to discover throughout the creative process, from writing, to the actual shooting, and finally the editing. They have to take what’s been proven to work, and then break it just a little.

Wolfe: Rewriting tropes was some of my favorite fun stuff with Black Christmas. Because it was mainstream (and technically a remake), we really did have to work a lot of those in, but we had this rare opportunity to poke fun. For instance, I can be a fan of Menstrual Power horror. Carrie is still one of my favorite movies. But in the hands of cis-male filmmakers over the years, a girl getting her period has given me a lot of eye rolls. I do feel that men romanticize menstruation as this magical thing, while people who actually menstruate are in the trenches for five days every month and not seeing it as so magical. That’s one of the reasons why we threw a girl on her period using a Diva Cup into the movie, which was a wink-wink for a lot of women. And then you get a quick shot of it in the end, and honestly we just thought it was hilarious. We got a lot of notes from women who watched it with their male partners who were utterly confused by what was happening, and it’s like, yeah, because menstruation is kind of boring and regular and isn’t some mysterious unspoken ritual.

Technological complications forced us to confront the trope of characters calling the cops. Everyone has a cell phone. How do you strand them? Some have to drop their phones. But eventually they’ll get a phone and be able to call for help. So with ours, we expanded the world a little bit. We made it so that when they finally did get through, there’s a reason why no help was coming — the cops were way too busy with other calls that night — and that allowed us to do a little misdirection. It’s what I called our “Silence of the Lambs moment.”

Farmer: For a genre that was created by old white men it’s not shocking that “female” nudity was not only a horror movie cliché but a destructive cliché. I won’t dive into the reasons because anyone reading this likely has the common sense to understand why. While the list of horror movie clichés is very long, “female” nudity is the only cliché that is often demanded on many productions. Look, I’m not against T&A, but to randomly toss nudity into a movie for no reason other than to objectify the actress always seemed like a dick move to me.

So in 1999, I wrote zero nudity in my first produced horror screenplay [Jason X]. No one really said anything because I think the assumption was that the powers that be would badger an actress into nudity later. And I know that badgering was attempted but it didn’t work. So in the 11th hour I was told I had to add nudity to the third act. I figured if I didn’t do as told someone else would and at least my doing it meant turning it into a self aware joke. Which I did. “Smoke pot and have premarital sex? We love premarital sex!”

Years later, I realized this was never a battle I was going to win, but I figured I could at least always justify the nudity, at least in my mind, and thus break the cliché of plotless disrobing. I also figured if I, the writer, was going to write nudity for my actress, then I’d better be willing to put my own ass on the line. Thus my bare ass is fully visible in My Bloody Valentine and Drive Angry. In fact, you know that cliché where you cut back after a sex scene and you just barely get a glimpse of the male’s ass as he pulls his pants up? Yeah, I didn’t do that. I left that ass out there to hang for a while. Thus to all those men who were used to slobbering over the actresses asked to bare it all, who found themselves extremely uncomfortable gazing upon my glowy white buttocks: Hahaha, fuck you.

Gottlieb: The “phone isn’t working” cliché has been done to death, but I once had a character who was by herself, and we already established she still had her phone on her. I wanted to do something different than rely on the old tried and true “I’ve got no signal out here” angle, so I had her take out the phone, dial a number, and be met with a recording that her service has been interrupted due to an unpaid bill. It totally worked for her character and I felt it was a relatable moment to the audience. Then she dies moments later. Unfortunately the scene suffered the same fate as it was cut later on.

Rivet: I think my ultimate subversion of a cliché/expected trope in Jackals might have cost us a lot of audience members when all is said and done. I think the audience was waiting for the predictable “turn-the-tables” moment, when the trapped characters figure out the weakness of the killer cult in the third act and get their revenge, but — spoiler alert! — that doesn’t happen. Some of the reviews even went so far as to say that they didn’t understand what the point was if the whole situation was hopeless and inevitable from the beginning, but that was kind of the point. Was it a miscalculation on my part? I guess it’s not for me to say.

Carolyn: My chapter in the anthology film Tales of Halloween was an exercise in subverting expectations. From the beginning, you know we’re building up to a jump scare — a trope in itself — so it was all about playing with the audience’s expectations of when it would happen. So we had Alex Essoe break her cell phone, stall her car, close a bathroom mirror, hear a creepy noise, see a door creak open… all just to misdirect the viewer so they wouldn’t know when the scare would hit.

Reddick: I don’t mind embracing a trope if it doesn’t hurt the story or make the characters seem silly. But I really try to subvert tropes if I can. I started with having a Final Guy in Final Destination. The great thing about tropes is you know what the audience expects to happen, so it’s really fun to try and twist it in some way just to get them jumping.

Even jaded horror fans can be fooled

CreepImage: The Orchard

Collins: The new Candyman has a brilliant bit where our heroine is about to enter a dark basement, only to offer a “hell no” and go elsewhere. And then it turns out the villain was upstairs anyway, meaning the basement might have been the better choice after all. For someone who has never seen a horror movie before, they’ll be scared with either scenario, but Nia DaCosta knew she needed to get a rise out of the veteran horror fans who have seen a thousand protagonists enter a thousand dark basements. Subverting a trope is a fine way to give weary genre aficionados a reason to perk up and realize that the filmmaker isn’t just playing to the cheap seats — they are putting in the effort to scare even the most dedicated horror buff, using our familiarity with these beats against us.

Serafini: I touched on this earlier with The Prowler, but I was also thinking of the new Candyman while considering this conversation. There is a character in that movie whose purpose feels largely expository, certainly intended to make the main character afraid and aware, but the ending manages to twist their purpose in a really strange and unexpected way.

Cox: The horror trope of loud noises at unexpected times has never been my favorite, but I understand why it’s a mainstay of the genre. That said, my favorite scare in David Bruckner’s The Night House turned this trope on its head when the heroine falls asleep with her head in her friend’s lap and in the next moment, is startled awake by cacophonous supernatural chaos. That auditory scare, combined with the heroine’s realization that hours have passed and she’s now all alone in her haunted house, turned a familiar trope into my favorite scare of the year.

Searles: When found-footage horror was proving to be a bonanza at the box office, filmmakers began panning for gold with every type of documentary or surveillance footage they could conceive of. This naturally created an influx of shaky footage from many amateur documentarians (the bane of the horror fan with motion sickness!), but it also inundated us with the opposite: the unmoving, unmotivated camera, recording everything that crosses its path passively and without interest. Home security systems, convenience store surveillance cameras, you name it. We became so inured to waiting for something of interest to cross in front of the static camera, that we stopped thinking about what might be behind it. I’m sensitive to spoilers, so I won’t reveal too much, but I will say that Creep (2014) features a sequence where an unmotivated camera moves, and the implications are terrifying. I was lucky enough to see that movie in a theater, and the rolling gasps from the audience as each person was roused from their torpor of found footage desensitization were glorious.

Farmer: Malignant comes to mind with this idea but I don’t really want to talk about that, because it’s too new and some folks may not have seen it yet.

Can horror’s tropes scare us forever?

In the EarthPhoto: Neon

Collins: No matter how much a filmmaker may innovate, at the end of the day, a trope is some variation on something we’ve seen before, and as viewing habits change, these clichés might result in an eyeroll and subsequent desire to distract yourself with something fresher. Everyone’s appreciation of a particular trope will vary; one might chuckle when they’ve seen their hundredth Survivor Girl try to start the hundredth car that needs three (always three) attempts to start before revving to life, while the person next to them might roll their eyes at how many times it’s been done.

And five minutes later, when the killer gets back up after seemingly being dispatched, it might be the other way around. Knowing which clichés need to be honored straight up and which need a little twist or subversion is impossible for any filmmaker to know with certainty. The thing that turns someone off from a particular film is undoubtedly going to be the moment that someone else decides it’s their new favorite movie.

Serafini: There are subgenres I like more than others. I mean, just hook slashers and gialli into my bloodstream. I know I’m far more forgiving of whatever clichés those movies might serve up, but I really don’t mind “the trope” as a concept across the entire genre and I don’t think I’ve ever disliked a movie because of a filmmaker’s over-reliance on them. And if it works for a younger audience, then who the hell am I to criticize?

Reddick: I can’t roll my eyes, because I’ve used some tropes myself, but I do like when a film avoids, or puts a spin on, an old trope. I see tired tropes most often from folks who aren’t diehard horror fans. You know the ones, “Let’s make a horror film because you don’t need stars, or a big budget…and when it’s a success I’ll direct the genre of movies I really want to direct.” Poseurs. But you can’t rag on tropes because they still work.

Donato: As someone who’s seeing triple-digits new horror releases a year, my awareness and scare endurance will trump anyone who’s seeing maybe three mainstream horror flicks in theaters during the same timeframe as a comparison. My appreciation of a jolt is always coming down to its execution, never base implementation. Someone who’s witnessing their first “slasher behind the opened fridge door” or “killer in your car when the overhead light flicks on” is going to emit such a howl when properly punctuated. Everyone has to start somewhere — Friday the 13th (1980) was not my first “villain jumps out of the lake when they should be dead” experience, it was Hatchet (2006).

Farmer: I appreciate when a filmmaker uses the cliche to fuck with me. When the mirror becomes the focus, when the music builds to draw me in… then nothing happens. Love that. No scare. No cliché. I like when the team uses my expectation and conditioning to build my anxiety… only to make me feel foolish for falling for it. Surprise and shock are a big part of horror, but that surprise and shock doesn’t always have to result in something happening. It can also be the result of expecting something to happen that doesn’t.

Rivet: A trope like the roadkill trope always works because the jolt it gives the audience. I don’t so much groan as I marvel at its repeated usage and repeated impact. Especially when huge, distinguished directors keep busting it out again and again. At this point, if someone is driving on a lonely road in a modern horror movie and they look a little distracted, I’m pretty much expecting them to hit some creature in the road, natural or unnatural, and for them to feel really bad about it afterwards.

Wolfe: I’m usually pretty amenable to these horror tropes popping up, because I want to see how a filmmaker is interpreting them. I’m of the mind that we’re all basically making the same movies over and over again, but the difference is the filmmaking vision.

Gottlieb: I want to see how that filmmaker can play with our expectations and even skewer them without turning into an outright parody of that moment. But I do also believe there is value in younger viewers being introduced to these tropes; avoiding them entirely isn’t just unnecessary but unrealistic. They are part of the cinematic language and it’s up to filmmakers to find interesting and clever ways to use them.

Cox: It’s great to see horror tropes subverted, but even when they’re not, I’ll accept it unless it’s half-assed. I won’t roll my eyes if a character running away from a killer trips over a tree root while they’re looking over their shoulder, but I will roll my eyes if that character trips over nothing while looking nowhere. I appreciate that there’s a younger viewer out there — and I demand only the best for them!