The series is ridiculous and over-the-top, but in a way that’s perfect for fandom

The Saw movies are the Fast & Furious of torture-porn franchises, as dedicated to doubling down on their original conceit as they are to their sincerely applied, ever-expanding lore. In the series’ ninth outing, Spiral: From the Book of Saw, someone appears to be following in the footsteps of The Jigsaw Killer, everyone’s favorite murderous philosophy major. Jigsaw has actually been dead since Saw III in 2006, but Spiral raises doubts about that statement: It’s the series’ second soft reboot in recent years, and a key question teased in its trailers is whether its grisly puzzle-murders are the work of a copycat, or someone connected to the original killer, John Kramer (Tobin Bell). It wouldn’t be a stretch to assume the latter, given how much the people behind the Saw series care about its sprawling continuity.

The Saw films can be neatly divided into three distinct eras, but they all share similar traits. By now, fans of the series expect three big things: elaborate traps resulting in self-mutilation, extended flashbacks to fill narrative gaps, and a major plot twist or three scored by Charlie Clouser’s thrilling composition “Hello Zepp,” which would be remembered as fondly as any John Williams theme, if the Saw films were better or more accessible to a general audience. Being a fan of these films means understanding they have a limited audience, but the fans who are ride-or-die for Jigsaw and his apprentices can at least bond over speculation about which minor character will be the next to don a pig mask and a black hooded robe, in order to kidnap people and turn their minor slights into elaborate torture games that make them appreciate being alive.

With every new Jigsaw killer comes not only the possibility of unexpectedly enormous traps, but the possibility of tenuous flashbacks to prior films. The connecting of dots that no one knew existed is what separates Saw from most horror sagas: The franchise’s winding, looping lore has become its central facet. Each new revelation is aimed at lengthening the series’ shelf life, but each one also comes with a host of meticulous in-world reasons for more sequels, each with their own ripple effects for multiple films.

And so, in true Saw fashion, we’re taking a trip down memory lane to see how all the pieces fit together, how the series evolved in scale and style, and how Jigsaw’s eight (yes, eight) serial-killer successors came to be.

The Jigsaw Era: Saw, Saw II, Saw III

Photo: Lionsgate

The first Saw, released in 2004, was directed by Aquaman helmer James Wan, and it stars the film’s co-writer, Leigh Whannell, who went on to direct Upgrade and The Invisible Man. Of all the franchise’s films, Saw has the most finesse: The series’ “torture porn” label doesn’t apply, since much of its gruesome imagery is implicit. It’s also the most intimate Saw film, with a relatively simple concept: two strangers with mysterious connections, Adam (Whannell) and Dr. Gordon (Cary Elwes), wake up chained to opposite ends of an industrial washroom with a corpse in the middle and numerous clues hidden all around, including an audio tape that tells them, in a deep, distorted voice: “I want to play a game.” Before long, they realize the only way to escape is by using a pair of hacksaws, not to cut through the chains on their ankles, but to cut through their ankles. The film’s tagline could not be more apt: “How much blood will you shed to stay alive?”

The first Saw is based, in part, on Wan and Whannell’s 2003 short of the same name, which is eventually folded into one of the feature-length version’s many flashbacks. The backstory lets Dr. Gordon explain the Jigsaw conceit to Adam, and to the audience. “Technically speaking, he’s not really a murderer,” Gordon says. “He never killed anyone. He finds ways for his victims to kill themselves.”

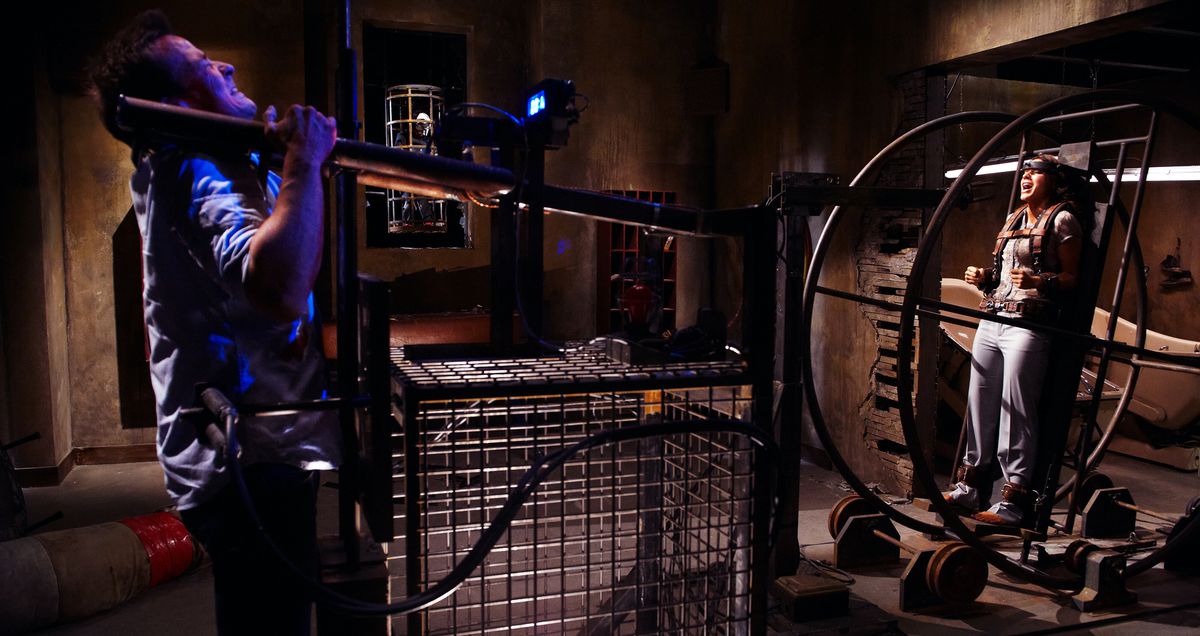

The production design is consistent across most of the series; its visual continuity is as important as its lore. The locations often feel dirty and dangerous, almost infected, which makes the self-mutilation all the more discomforting. The films operate in the shadow of Vincenzo Natali’s 1997 indie Cube, an existential sci-fi horror film about deadly industrial escape rooms, and Adrian Lyne’s 1990 feature Jacob’s Ladder, whose demonic head-shakes were borrowed for Saw’s fast-forwarded secondary traps. The series also takes music and design cues from early 2000s nü-metal. The band Taproot in particular feels like an overt influence; Its music video for “Poem” mirrors the series’ decomposed look, while the video for “Time,” with its literal writing on the wall, seems to have influenced a trap in the first film.

The first Saw is great at building tension, and its final twist is genuinely unsettling: the voyeuristic Jigsaw, revealed to be one of Gordon’s cancer patients, is posing as the corpse in the bathroom the whole time. While some of Saw’s tropes and flourishes re-appear in later entries, though, Saw II is the entry that really sets the franchise’s template, from its sickly green tinge to numerous twists that are mirrored in the rest of the series, to varying degrees of success.

Based on a standalone script by Saw II-IV director Darren Lynn Bousman, with some polishing by Wan and Whannell to fold it into Saw continuity, Saw II ups the ante from an escape room to an entire escape house, with criminals wandering from room to room and playing elaborate survival games. Elsewhere, dirty cop Eric Matthews (Donnie Wahlberg) is forced to listen to Jigsaw espouse his philosophy, as footage from the house-of-horrors plays out on security screens. (Matthews’ teenage son is one of the participants.) However, it turns out the video was pre-taped, and all Matthews needed to do to get his son back was sit tight and listen to Jigsaw ramble, instead of torturing the decrepit old serial killer until he reveals the location of the house, sending Matthews to his doom. It’s the first of the series’ timeline twists, and the only one that really works.

Locations in the Saw movies often feel dirty and dangerous, which makes the self-mutilation all the more discomforting.

“Your son is in a safe place,” Jigsaw assures Matthews numerous times — before his son is revealed to be in a literal safe, right next to where they’re sitting. It’s the first of many dreaded doublespeak twists throughout the franchise, where Jigsaw outsmarts his victims with words. The film also establishes the most important twist of all: the apprentice twist, when it turns out that one of the game’s repeat victims, Amanda (Shawnee Smith), a minor character from Saw, was so spiritually transformed by her first ordeal that she became a Jigsaw devotee.

Saw III, while a lesser film than its predecessors, helps tighten and structure the second film’s meandering walkthrough concept, while also expanding its scale: new protagonist Jeff (Angus Macfadyen) undergoes a series of tests in a giant factory, where he’s invited to forgive and rescue various people responsible for his son’s demise. Every subsequent film follows this structure — a central character going from room to room, playing one “game” at a time — but Saw III drags its feet as it cuts between Jeff and another, less interesting game happening nearby, as a doctor, Lynn Denlon (Bahar Soomekh) tries to keep a bedridden Jigsaw alive long enough for Jeff to succeed.

Even though the film definitively kills Jigsaw (and his apprentice Amanda, too), it plants plenty of seeds for later entries. It also establishes a major shift in the series’ visual priorities. Where gore was previously a byproduct of its storytelling (and used somewhat sparingly), here, the filmmakers place it on full display. They not only design traps to more explicitly mangle the human form — among them, a limb-twisting torture rack — but the film also features a gratuitous scene of Lynn performing brain surgery on Jigsaw, shot in extreme close-up. But even this sequence pales in comparison to what came next.

The Apprentice Era: Saw IV-VI, Saw 3D

Photo: Lionsgate

2007’s Saw IV opens with Jigsaw’s autopsy, shot in excruciating detail. It firmly shifts the Saw series’ focus toward satiating a thirst for gory imagery. This shift was also marked by a creative change; while Bousman stayed on as director, Wan and Whannell, who penned the first three films, were replaced by Patrick Melton and Marcus Dunstan, whose four Saw entries picked up right where each of their predecessors left off. During this period, the series began to feel like an extended police procedural about apprentices on the run.

Saw IV expands the “walkthrough” concept even further, sending Lt. Daniel Rigg (Lyriq Bent), a minor character from Saw II, on a city-wide scavenger hunt through Seven-esque scenarios. The film is visually incomprehensible, but it features a few nice flashbacks to Jigsaw’s early days as an engineer, his life with his ex-wife Jill (Betsy Russell), and the gloomy events that led him to design creepy puppets and create his earliest, most rudimentary traps. The series’ new creative mandate seemed to involve more bloodshed, and more backstory.

But even though it’s overloaded with Jigsaw flashbacks, the film has an apprentice reveal that still feels completely out of the blue — Detective Mark Hoffman (Costas Mandylor), who appeared in a single scene in Saw III, vows to carry on Jigsaw’s work. That sets the stage for the remaining sequels. Pretty much anyone in these films could turn out to be a Jigsaw apprentice, for any reason, and the gaps could be filled in later. Saw IV also has a timeline twist that sets the poor precedent of twists for the sake of twists, with a reveal meant exclusively for the audience: It turns out Saw IV takes place concurrently to Saw III, and their events converge at the end. The film’s ridiculous climax, therefore, depends on Jigsaw predicting that about six different characters, three of them cops, would all shoot each other at precise moments. It’s the Saw equivalent of Saturday Night Live’s “Dear Sister” parody sketch.

Saw V reins in some of these sillier elements. It feels more narratively restrained, to the point where it’s something like a filler episode, though it’s no less visually gruesome than other installments. (For instance, it features a man being sawed in half by a giant pendulum.) Directed by series production designer David Hackl, the film features three barely cohesive plots, two of which are somewhat interesting. On one hand, there’s a new walkthrough trap, where five characters must figure out the events that bind them. On the other, the film also has a series of extended flashbacks which reveal how Hoffman, once a vengeful Jigsaw impersonator, was roped into working with the real Jigsaw as early as the first film. Unfortunately, the plot connecting these two threads — an FBI agent on Hoffman’s tail — is one of the many uninteresting cat-and-mouse chases Melton and Dunstan seem to enjoy.

The overarching story of cops chasing the new Jigsaw continues in Saw VI, as Hoffman goes off the rails and turns against Jigsaw’s twisted lessons on the value of human life. However, it kicks things up a notch as the only Saw film with something relevant to say, taking aim at America’s brutal healthcare industry. It also grounds its story in something personal for Jigsaw: Its central victim is the merciless health-insurance CEO who denied John Kramer coverage when he was still alive. It’s the first time in the “apprentice era” where it feels like Jigsaw being dead isn’t just a corner the series wrote itself into. Instead, the plot feels like vengeance from beyond the grave, as the CEO is forced into brutal games where he must choose which of his employees will live or die, as his cold, calculating policies become death traps. On the lore front, Saw VI finally reveals the contents of a letter we saw Hoffman leave Amanda in Saw IV, which we first saw her read in Saw III, and which it now turns out concerns events from before the first film. It’s a continuity nesting doll.

Pretty much anyone in these films could turn out to be a Jigsaw apprentice, for any reason, and the gaps could be filled in later.

Saw VI was directed by Kevin Greutert, who edited all the previous Saw entries, and it’s arguably the best film in the series. However, Greutert also directed the worst Saw film to date, Saw 3D, or Saw: The Final Chapter. The 3D conceit alone made the promise of gore essential to the marketing — plenty of guts fly directly at the camera! — and the whole endeavor feels rushed and cheap. At least it has an interesting central character, Bobby Dagen (Sean Patrick Flanery), who poses as a Jigsaw victim, makes money off TV and book deals, and leads group therapy sessions for victims from other films. It’s the first real look at how the public at large responds to the Jigsaw killings. However, the film’s traps are all tensionless, as the series finally makes them large and showy enough to hit a point of saturation. Elsewhere, more cops hunt Hoffman, while Hoffman in turn hunts Jigsaw’s ex-wife, who turned out to be an apprentice herself in Saw VI.

The film nominally pays off a theory fans had been discussing for years: Without buildup, it reveals the sudden apprentice twist that Dr. Gordon has been working with Jigsaw ever since he sawed off his own foot in the first film. Of course, Gordon had been absent on screen for six entries, so this twist is revealed through flashbacks to nearly every preceding film. And in an act that feels like Saw’s series roots wiping out its later iterations, Gordon nixes the Hoffman problem with ease, abruptly ending the apprentice plot which ran through all four of Melton and Dunstan’s films. This was the duo’s last entry in the franchise.

Gordon also has two other pig-masked apprentices in tow. Who? How? Why? You’d think the next film would answer these questions, as is the series’ M.O., but Saw 3D was, in fact, the final chapter for a while. After releasing a new Saw film on seven consecutive Halloweens, the franchise lay dormant for another seven years — until its relaunch in 2017.

The Post-Post-Jigsaw Era: Jigsaw, Spiral: From the Book of Saw

Photo: Lionsgate

When 2017’s Jigsaw begins, there’s been zero Jigsaw activity for a decade. Half the story follows five victims walking through a barn full of comically elaborate traps, while the other half features more boring cops and a pair of medical examiners trying to identify new victims. One of these examiners really ought to have been the main character — Eleanor (Hannah Emily Anderson), one of many online Jigsaw enthusiasts who collects old traps, hinting at a larger, more interesting world — but she’s relegated to a minor role.

In addition, the film’s eye-rolling twists are the first in the series that feel like they make prior entries worse. A timeline twist for the audience reveals that even though the events in the barn are crosscut with the police investigation, they actually happened a decade ago. The barn turns out to have been Jigsaw’s earliest game — Kramer, who was heavily featured on the posters, unsurprisingly appears alive and well. Meanwhile, in the present, an identical game unfolds in the same barn, though it isn’t shown onscreen. It’s also another apprentice twist, since it turns out medical examiner Logan Nelson (Matt Passmore) was one of the victims in the barn 10 years prior. But Jigsaw, in a move completely antithetical to his character, took pity on Logan and saved him from the game, and they’ve been working together ever since.

The film features a number of complicated, Rube Goldberg-esque traps which are all brightly lit, and more silly than scary. The barn is reminiscent of the series’ later entries, where the scale of Jigsaw’s games expanded from cramped rooms to entire factories. But Jigsaw loses the signature gritty, lived-in feel. Everything is a bit too clean and polished. The film is sterile, and visually discontinuous with the rest of the franchise. In addition, it shoots its own lore in the foot by revealing the barn to have been some secret original game, before all the others. This robs John Kramer of his simpler scale in earlier films (and in flashbacks as the series went on), when his traps were grimier and more DIY, and it robs the franchise of its gradual descent into full-on industrial mayhem. It may be deliriously fun to watch a Jigsaw victim be mangled by a blender the size of a jet engine, but it’s strange to think that John Kramer scaled down to a simple bathroom full of chains after this elaborate madness.

The dedication to building continuity keeps fans on their toes, as they engage in one of fandom’s favorite pastimes: speculation.

Jigsaw, the first Saw film written by Josh Stolberg and Pete Goldfinger, failed to relaunch the franchise in 2017, but the screenwriter duo has a second chance with Spiral, which also returns Bousman to the director’s chair. It’s the first A-list Saw movie, featuring major stars like Chris Rock and Samuel L. Jackson. It even has its own tie-in single by 21 Savage, a hip hop remix of “Hello Zepp”. But in spite of the money behind it, the film looks far gaudier than Jigsaw, and as garishly color-corrected as previous entries. Saw movies aren’t meant to look expensive, even if they are.

But while Spiral feels visually continuous with the rest of the series in a way its predecessor wasn’t, it doesn’t have the same obsession with narrative continuity as the other sequels. It features gory traps, but it can’t help but feel like it’s reading from an entirely different “book of Saw” than most long-time fans, whose lasting appreciation for these films comes, at least in part, from just how much time the movies spend trying to justify their own existence.

Every retroactive reveal in a Saw film, no matter how silly, is framed as an intentional choice, made by villains whose actions are otherwise so over-the-top that they’re disconnected from recognizable human impulses. But when the franchise starts filling in the narrative gaps, the killers’ outlooks suddenly click into place, whether through a dozen flashbacks revealing an apprentice’s attempts to cut ties with Jigsaw, or a former addict becoming addicted to the brutality of torture over the course of several entries. By making these rationalizations the central point of each flashback, the series is able to pull off new and ridiculous plot twists — and only justify them in retrospect.

This dedication to building continuity keeps fans on their toes, as they engage in one of fandom’s favorite pastimes: speculation, predictions, and wild guessing. With the Saw series, they’re given the opportunity to deduce which existing character will next be force-fitted into an origin story about living life to the fullest by committing a whole bunch of murders. In an entertainment landscape where fan engagement is the key to a successful franchise, it’s notable how much of this series has been about fooling the audience — and inviting them to prove they’re too clever to be fooled, to tease them with the possibility of getting out ahead of a narrative that’s both predictable in its obsessions, and unpredictable in its unlikely tricks. It’s the best part of the Saw franchise: the sprawling continuity that turns these films from mere torture porn into torture porn with a side of soap opera.