The latest Call of Duty campaign plays games with history

About two-thirds of the way into Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War’s campaign, in classic Call of Duty fashion, the game shifts in perspective away from its main protagonist, a CIA operative called “Bell,” to a man named Dimitri Belikov, an American mole embedded within the KGB’s headquarters in Moscow. As Belikov, you can pop into offices and eavesdrop on chain-smoking analysts variously digging through newspaper clippings, listening to U.S. news broadcasts, or strategizing with one another about intel. In spite of the building’s grandiose architecture, with its soaring central atrium draped with red flags and tall portraits of stoic party leadership, the space still feels largely pedestrian, like any office building full of people working on their tiny little piece of a massive and self-propelling bureaucracy. On the other side of the world, in Langley, the same sorts of people are doing the exact same sort of thing. Knowing this, this moment in the game offers the player a kind of mirror, a visual recognition that the people who are your ostensible mortal enemies are really just another version of you.

And then you switch back to your operatives, strap on some flak armor, pick up your machine guns and light the whole place up. The same halls that were once full of the peaceful busywork of war now transform into the stage for the bullet-scarred and bloody job the series has always been more comfortable taking part in.

It’s a running theme throughout Cold War–a confusing split laid right down the middle. On the one hand, the game seems to recognize the arbitrary divisions of the conflict, its false messaging and self-fulfilling propaganda. On the other, it heaps upon the player an endless stream of heavy-handed jingoism, of defending the “Free World” from the evil, Communistic threat. The main task of the game, after all, involves using action spy-movie dramatics; flying around the world, connecting threads on a corkboard, infiltrating behind enemy lines, torturing and maiming suspects, all to prevent nukes from falling into the dreaded enemy’s hands—a threadbare premise the Call of Duty games have relied on countless times before.

Image: Treyarch, Raven Software / Activision

Few parts of the plot are delivered with subtlety or in half-steps. Early on, our heroes, waiting in a government boardroom, are interrupted by double doors swinging violently open as the newly inaugurated President, Ronald Reagan, strides confidently into the room. The soundtrack swells patriotically as the camera gets in close on his exhaustively detailed face, the room’s light picking up his sun-baked wrinkles and glancing off his piercing baby blue eyes. Effortlessly masculine, idealized and paternal, he sweeps aside the peevish concerns of his worrying generals and gives your team carte blanche to hunt down the secret Russian operative “Perseus” by whatever means necessary, legality and plausible deniability be damned.

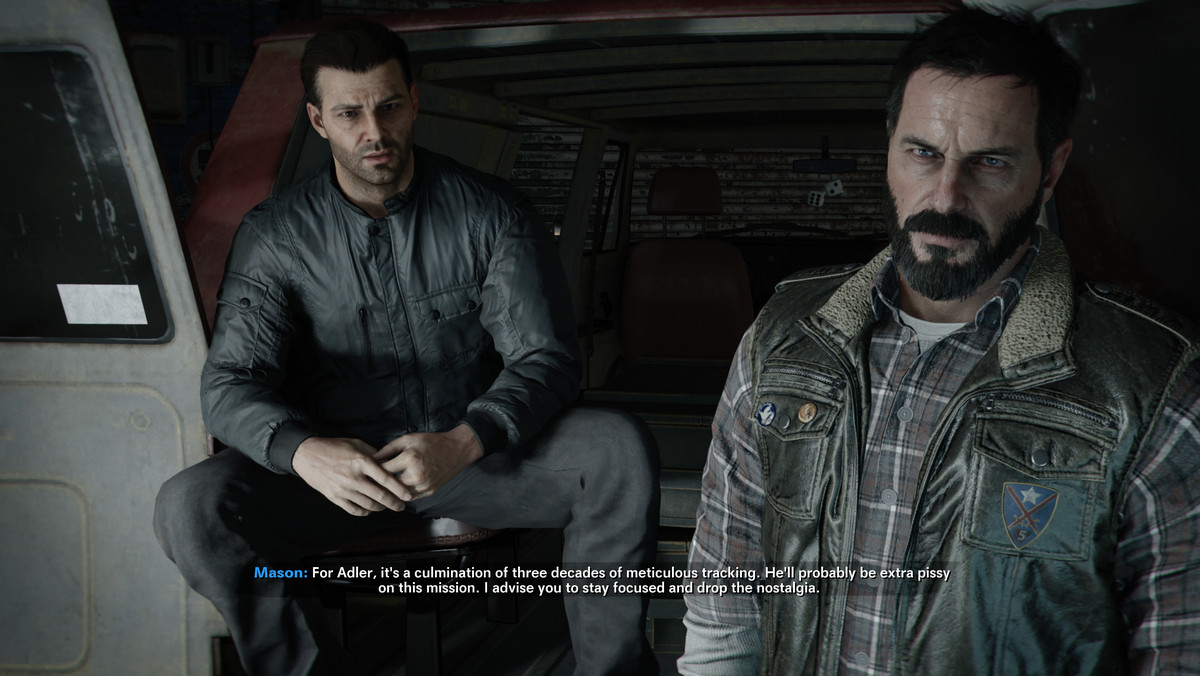

Though Russel Adler, the team’s leader, evokes the cool-headed stoicism of a Robert Redford-type, and most of the other new additions to the team have a reasonable amount of dimensionality, the series’ staples Frank Woods and Alex Mason reflect Reagan’s cartoonish extremes and remain just as faux-edgy and ratcheted up as they were in the previous Black Ops titles they starred in. Consummate and irredeemable bros, fist-bumping, one-lining and smirking their way through the game’s missions; their aggrieved bloodlust feels out of place next to the more delicate and buttoned-up aesthetic of spywork the series’ fifth installment seems newly interested in foregrounding. They sit uneasily next to the darkrooms and briefcases, the leather jackets and listening devices snatched from recent dramas like The Americans and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

Meanwhile, the player’s character, “Bell,” or, according to my own playthrough: “Yussef ‘Bell’ Cole,” participates mostly as an outside observer, detached, in myriad ways, from the plot’s core exigencies. This is partly because Bell’s characteristics are arbitrary and variable. You’re able, by means of a CIA case-file that pops up in the beginning of the game, to freely alter their backstory and psychological profile. Pulp-novel pathologies like “paranoid” or “aggressive behavior” won’t have any affect on how your character relates to others, but will grant them access to attached mechanical perks like fast-reloading or extra health.

Image: Treyarch, Raven Software / Activision via Viaggio247

Your character’s fungible identity fits neatly with the type of spywork missions you engage in. There’s the previously mentioned mission involving subterfuge within KGB HQ, for which Cold War offers the player a novel set of tools: instead of immediately rushing in guns blazing, you must first set the stage with a stealthy approach, getting to choose from a bevy of underhanded options, including blackmailing a general, hacking files, and interrogating a political prisoner. It’s not until you’ve successfully navigated through this refreshingly espionage-forward section that you can return to the running and gunning that is the game’s mainstay.

Another mission, “Redlight, Greenlight,” takes place inside a massive Soviet bunker, where for live-fire training drills, their military has built an impressive replica of an American town (named, appropriately, Amerika Town), complete with period-appropriate arcades, burger joints, and miles of vibrant pink ’80s neon. Though it is preceded by the prefabricated fake town of another first-person-shooter, Titanfall 2 (featured in its brilliant “Into the Abyss” mission), Cold War manages to take the same premise a step further by highlighting the inherent uncanny goofiness of military war games, even including playable game cabinets in the Amerika Town’s arcade as an additional layer of games within a (war) game within a (video) game. Navigating among the colorful cabinets, your side trades shots with the Russians, struggling to distinguish them from the town’s numerous cardboard standees and mannequins, unable to distinguish flesh and blood from flat symbolism.

It’s all theater that knows it’s theater

Much of the game leans into this polished, if artificial, one-dimensional feel. Rather than taking place as naturalistic beats along a linear narrative, Cold War’s missions feel more modular, represented as stacks of photos, scribbled code sheets and newspaper clippings pasted up on a wall in your safe house. Hidden in most missions are collectible evidence items which you can bring back to the safe house and use to solve the small, escape-room style puzzles on the evidence board, which are necessary to complete a series of side missions (of which, sadly, there are only two).

The members of your clandestine team will pace around the safe house on pre-programmed routes, sometimes going up to each other and engaging in hushed conversations, like actors on an immersive set. One of them might answer a phone call and hold the receiver in place, saying nothing and staring out into space until you interact with him. Little distinguishes them from the cardboard figures of Amerika Town. Within missions, they’ll belt out sardonic quips and jingoistic inculcations, all with the same emotionless reserve–“We don’t sit back and hope for the best, we make the best happen” or “Some of us have crossed the line, to make sure the line’s still there in the morning”–each entreatment meant to draw the player into the game’s ideology and which belie the truth that the game doesn’t seem to believe in its own ideology. It’s all theater that knows it’s theater.

[Warning: The following section contains full spoilers for Call of Duty Black Ops: Cold War.]

Image: Treyarch, Raven Software / Activision via Viaggio247

This is made clear in Cold War’s final moments. It’s revealed that your character, Bell, was previously an agent working for Perseus, and was captured and manipulated by CIA mind control to switch sides. After running out of options, Adler and his team go to work interrogating Bell to try and undo their conditioning, but it ultimately comes down to a choice that the player must make: tell the CIA the true location of the nuke launch site or give them a fake one, where you can direct Perseus to set up an ambush for the people you spent the whole game fighting alongside. The character of Bell, driftless and confused for so long, without any real stake in any of the missions, is now given the ultimate stake, now becomes the fulcrum around which the remaining events of the game occur.

But it’s a choice that functions less within the space of the game’s narrative than as conversation between the game and the player. It’s the player who is asked to choose, who is no longer able to hang back as a casual observer. The weight of this choice is something that the hollowness of Cold War’s confused message, its simplifying of decades of historical complexity into superficial spy games, isn’t quite able to bear.

In a previous Call of Duty installment, Advanced Warfare, players were asked to “Press F to pay respects” to their fallen brothers in arms. It was silly and melodramatic, and was rightly maligned, but it still meant something. Cold War, meanwhile, is utterly unable to hide the absence of meaning in the actions you perform. At one point you’re the audience for Reagan’s saccharine propaganda. At another, Gorbachev woodenly wags a finger about the evils of capitalism; it’s hard to take either of them seriously, impossible to fully fall under the spell of a game that wields historic imagery as a shiny piece of aesthetic, as a world with which to spin clever spy stories told by smooth operators behind tinted shades, not a history with which to reckon, full of operational failures and far too many bodies to count.

Image: Treyarch, Raven Software/Activision

When faced with the choice of whether or not to betray Adler’s team, I hesitated only briefly before choosing to sell them out to Perseus. Leading up to this choice, the player is led through a dream sequence stomping through the rice paddies of Vietnam while Adler’s voice booms from somewhere above. He’ll direct you to take a left or a right, to go down a tunnel or climb up a hill. You can ignore his directions, struggle against them, and watch as the lucid dream begins to unravel into nightmare: cables and server towers appear between trees, the floor transforms from mud to concrete to the lacquered tiles of an operating room; you fall into a deep cave and are attacked by zombies.

Even resisting the programming winds up being its own kind of programming

Then, as your character nears their breaking point, a door opens to your side, revealing a small dark room with an arcade cabinet in it. It’s a game of Kaboom!, which involves catching an endless cascade of bombs as they are dropped by a tiny figure at the top of the screen. Offscreen you can hear your handlers sigh in relief as Bell’s stress levels ease back down to the baseline, absorbed, as you are, by a simulated arcade game from 1981. Even resisting the programming winds up being its own kind of programming.

Though siding with Perseus may seem like the bad ending–you do nuke half of Europe, after all–it also works as an admission, a peek behind the curtain. The good, theatrical version of things means switching sides to work for the good guys, swooping down on Perseus’ base and saving the world at the last moment. But it feels as naive and simplistic as catching bombs in a barrel in Kaboom! It feels as unmoored from reality as solving spy puzzles in your safe spy house. Turning around and blasting your ex-teammates, meanwhile, watching them fly back in dramatized John Woo-style slow motion, may seem just as artificial, but still serves as a tiny form of rebellion, like taking your hand off of the arcade stick, your fingers off the buttons. If the belief systems within this game are as muddied as they clearly are, if the politics of the Cold War are as frustratingly self-defeatist and un-self-aware, what reason is there to engage in good faith? And so I found myself impressed that the game, in the end, also leaves space to engage in a different way. When asked to make a choice, I appreciated being able to make one that more closely resembled my own, even if it had already been programmed and accounted for.

Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War was released Nov. 13 on PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Windows PC, Xbox One, and Xbox Series X. The game was reviewed on PC using a download code provided by Activision. Viaggio247 Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Viaggio247 Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Viaggio247’s ethics policy here.