And that may explain how it became a blockbuster hit

By all accounts, Warner Brothers’ Godzilla vs. Kong is a hit, though how much of one is still a little murky. Still, a $49 million seven-day box-office total and a generally positive audience response bode well for the uncertain future of the MonsterVerse, and the uncertain future of movies in general. The film’s success is well-deserved — it’s a joyous extravagance suffused with neon, and director Adam Wingard never met a plot twist he wasn’t willing to take with gusto. It also has big messages about humanity’s need to get its act together in the face of existential crisis, but the audience would be forgiven for not noticing that in the scrum of two monsters boxing each other on top of a goddamn battleship.

Wingard has been open about how his love of bonkers filmmaking led to this point. Though not all of Godzilla vs. Kong gels into a cohesive vision, and the plot has a number of cul-de-sacs that bog down the middle of the film, its maximalist approach to big monsters makes an easy kind of sense. And it hearkens back to the most interesting run of Godzilla movies: the Shōwa era, where the monsters stood in for the messy, complex anxieties of Japan’s first post-war generation, and the serious themes of environmentalism, fear of invasion, and humanity’s hubris were allowed to coexist with the burly guys in the rubber suits.

The long, rocky road to embracing Godzilla’s gonzo roots

Photo: Warner Bros. / Legendary

The MonsterVerse’s financial success was far from a foregone conclusion. Leading up to the release of Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Godzilla, the franchise seemed like it maybe just didn’t translate to Western filmmaking, thanks in large part to Roland Emmerich’s 1998 Godzilla. That was more of a dumbed-down Jurassic Park than a true Godzilla picture, with its “Life finds a way” twist and its chintzy T-Rex design, which looked better on Taco Bell commemorative cups than onscreen. Perhaps in reaction to that film, Edwards chose to ignore decades of big-should-be-bigger, ungapatchka storytelling in favor of a straight-faced nuclear parable that adopts the imagery of the Fukushima disaster without having much to say about it. His film occasionally strikes awe into the audience, but he ultimately isn’t very interested in letting them have fun.

The Kong side of the MonsterVerse fared a little better: Kong: Skull Island has a go-for-broke approach to critiquing the American military’s postcolonial desire for forever war. Still, it’s a mixed bag: the combination of Brie Larson and Tom Hiddleston imbues the film with powerful bisexual energy that rivals 1999’s The Mummy, and John C. Reilly turns in a charming performance as a marooned World War II vet who chose peace. But the tone bounces between self-importance and mean-spirited carnage in a way that ultimately undermines its themes.

Then came Michael Dougherty’s 2019 installment Godzilla: King of the Monsters, which is po-faced and dull in its approach, even as it moves the needle in the right direction in a few key ways. It embraces the excess of Shōwa-era Godzilla movies, but not their daffy charm, again seemingly out of a desire to play it safe. The film unfolds as though Dougherty was embarrassed by the franchise’s heritage, but still beholden to it. By the time Sally Hawkins’ character is unceremoniously squished out of the movie in the first act, viewers are ready to go with her.

But now we have Godzilla vs. Kong, which doesn’t have an embarrassed bone in its very big, very silly body. Wingard has no pretensions about being serious. He jettisons the tone of the Western Godzilla movies that preceded him, and looks to the earliest Godzilla films for inspiration. His film is a fitting homage to the legacy of kaiju movies, and a fitting first blockbuster for a post-pandemic world.

Shōwa Godzilla is really weird

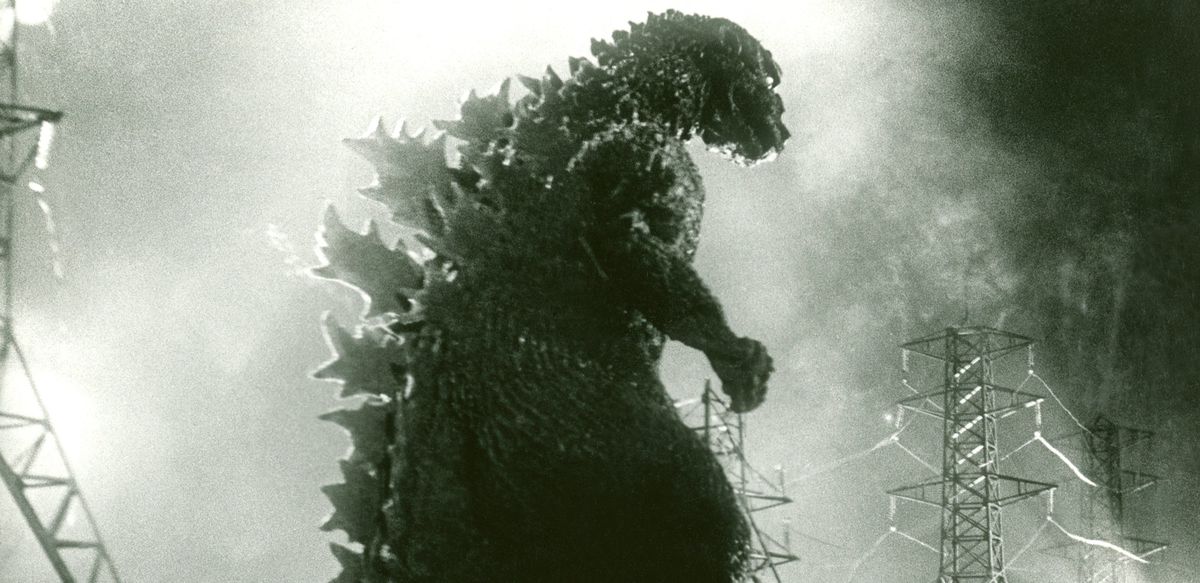

Photo: Toho Company

The Shōwa era of Toho Company’s Godzilla series covers the original 1954 movie up through 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla. It spans 15 films and a number of pivots for the giant monster, most notably 1962’s soft reboot King Kong vs. Godzilla, which moved away from the straight-faced nuclear trauma of the first two entries, and set the template of big monsters pile-driving each other in new and inventive ways.

Though it’s included in the Criterion box set that collects all of the films, King Kong vs. Godzilla is one of the few in the series not available to stream on HBO Max, either because of the problems with its master cut stemming from a botched re-release edit, or because it features a prolonged, embarrassing segment where hundreds of Japanese actors put on brownface to portray indigenous people, and are easily bribed by a landing party’s cigarettes. It really is an execrable film, despite the best efforts of actor Tadao Takashima, who puts in a winning turn as the comic-relief studio-executive villain who thinks bringing Kong to Japan would be a good way to juice his science program’s poor ratings.

Despite the stumble, the decade-long franchise run that followed King Kong vs. Godzilla is phenomenal popcorn entertainment that embraces the silliness of its premise without sacrificing a desire to explore serious themes. There’s a deadpan earnestness at work in the films — the creators know they’re making silly stories, but there’s a joyful sincerity in the approach, and that’s what makes their maximalist approach to storytelling work so well. (Weather machines! An astronaut in love with a robot! Extended songs sung to Mothra by tiny telepathic twins that fit in a suitcase!) Viewers are already suspending their disbelief the moment Godzilla stands straight up in an ocean that would surely be deeper than he is tall, so why not keep suspending it?

This isn’t an argument for brain-off, passive viewing. There’s a profound difference between mindless cinema and cinema that asks you to think about it as experiential or a work of style. All stories establish their grammar, then use that grammar for emotional payoff, and the grammar of Shōwa Godzilla films is singular. With relatively meager budgets, the miniatures and rubber suits are more impressionistic than realistic, and the way miniatures are used in establishing shots conveys humanity’s smallness next to the lumbering monsters.

This technique also gives the movies a toybox vibe, which the films leaned into, dressing up the sets in pastels. (Wes Anderson fans should love the playful designs of Shōwa-era Godzilla movies.) Watching these films today, it’s easy to laugh at how cheap it all looks, but it’s just as easy to get caught up in the spectacle, and it’s clear that the filmmakers were in on the joke without sacrificing their exciting stories.

Photo: Toho Company

The most fascinating of these is Godzilla vs. Hedorah. It may be the most outré of the Shōwa Godzilla movies, featuring hippie freakouts, animated segments, a sludge-monster with acid attacks that can melt people down to their bones, Godzilla using his breath to fly through the air (!?), and a Bond-style opening song about how pollution is going to kill us all. It’s an excellent film specifically because of how little chill it has. The prolonged final battle takes place in darkness, which is uncommon, and allows for the striking image of Godzilla’s breath against a pitch-black background — reminiscent of the neon-suffused images of Godzilla in GvK’s climactic Hong Kong battle.

There are missteps along the way, of course. 1967’s Son of Godzilla has its charms, but the junior Godzilla looks like a slightly melted version of Jack Lemmon. He’s upsetting to look at, and even more upsetting when he’s riding on daddy’s tail. The decision to kill Mothra and replace him with a larval child probably saved a lot of trouble for the puppeteers, but there are only so many ways for a worm to spit goo in interesting ways. Godzilla waving his arms around takes on a slapstick quality in some of the clunkier scenes, and many of the fights devolve into two monsters throwing rocks back and forth. But even the flaws end up contributing to the feeling that Toho’s first priority was heartfelt audacity. It’s a rich, decade-long textbook of bonkers filmmaking.

Almost every element of Godzilla vs. Kong has an analogue in a Shōwa Godzilla movie, from the cave paintings depicting an ancient rivalry to the amateur journalists infiltrating science facilities to the bluntly ridiculous dialogue. (“I bet Godzilla would be mad if he saw this,” says a boy in Godzilla vs. Hedorah, which is at least as good as Kyle Chandler’s straight-faced “Creatures, like people, can change” in GvK.) There’s a moment late in every Shōwa Godzilla movie where the camera perspective shifts upward, bringing the audience to the scale of a kaiju instead of the ground’s-eye view, which is largely abandoned save for a few random reaction shots, as though city destruction were a form of televised wrestling. Shōwa kaiju are almost never framed from ground-level during the last 20 minutes, which is part of why it’s so thrilling when Wingard throws some Kong POV shots into GvK — it feels like an evolution of a longstanding tradition.

At the end of each Shōwa Godzilla film, the threat ended, Godzilla lumbers back into the ocean, perhaps with a small child waving at him. He’s a stoic god whose work is done. In all, it’s perhaps the most inventive, daffy stretch of science fiction filmmaking in history, and Godzilla vs. Kong feels so gloriously overstuffed because Wingard is determined to do it all in one movie.

Why Godzilla hits so hard in 2021

Photo: Warner Bros. / Legendary

The Shōwa-era films were unapologetically about something while still being blockbusters, and Godzilla vs. Kong takes that approach too. Its human characters are largely useless, which seems to be the point — they’re living life in miniature compared to the Titans, and any attempts to control a Titan inevitably end in disaster.

Their concerns are insignificant, too; with the world coming down around his ears, Bryan Tyree Henry’s Bernie is still inviting people to guest on his podcast. The film’s general disdain for humanity is most apparent in Walter Simmons, the Donald-Trump-meets-Elon-Musk villain (complete with his daughter/minion Ivanka Maia). Walter, played with sneering hubris by Demián Bichir, thinks domination and control while preserving life for the rich is the key to success amid ecological disaster.

One hallmark of the Shōwa era is that the heroes are usually scientists, journalists, or children, all of whom are concerned with doing right by the monsters — the characters who think use of force is the way to go are relegated to the sidelines, or actively presented as villains. Like its forebears, Godzilla vs. Kong is presenting an argument about the use of adaptation and mitigation with regard to unavoidable change. That seems fitting after a year of pandemic and a climate crisis that has experts re-examining human impact on the environment yet again. Past a certain point, humans can’t use technology to bully life into what they want it to be — they either have to avoid it, live in harmony with it, or learn to change.

That’s what characters had to do in the Shōwa Godzilla movies, too, until the thing that scared them became the defender of their island nation and a symbol that transcended the films themselves. The beast born from nuclear anxiety became something like a friend — by the mid-’60s, a character in a Godzilla movie was more likely to welcome Godzilla’s arrival than to run from it. “Living in harmony with what scares you” sounds as much like a line from a 2020 campaign speech as it sounds like the ultimate message of a kaiju flick, because these themes have become even more pressing in the last decade.

Today, Godzilla is a potent metaphor the same way zombies were during the Cold War. He’s a trauma response, after all, awakened by mankind’s hubris and unwillingness to work together for the common good. We’re beginning to emerge from a long, dark period of our planet’s history, and the future is just as uncertain. We need stories that address that without being a grim, depressing slog. We need stories that revel in the chaos of our modern lives without giving up. Most of all, we need the catharsis of stories about big beefy boys who punch each other good. Godzilla vs. Kong is a movie made by a team who tried to make it the absolute most — the biggest, the loudest, but also the most respectful of the franchise’s history. In the process, they made it into the first Hollywood movie to actually wield the real power of Godzilla.