A panel of editors discuss how the field has already changed, and what’s coming next

What does the future hold? In our new series “Imagining the Next Future,” Viaggio247 explores the new era of science fiction — in movies, books, TV, games, and beyond — to see how storytellers and innovators are imagining the next 10, 20, 50, or 100 years during a moment of extreme uncertainty. Follow along as we deep dive into the great unknown.

When Viaggio247 talked to a series of professionals about the biggest ways science fiction has changed over the past decade, they noted shifts in everything from publishing trends to popular themes to the use of social media to build communities. But every one of them touched on one major idea: For the last 10 years, science fiction literature has been radically diversifying, with more stories and books being imported from other countries, and more LGBTQ authors and writers of color being recognized and celebrated in the genre than ever before.

But what does that actually mean to the field? It’s easy to say “Science fiction is more inclusive than it used to be,” or “authors are more diverse.” But how is that actually effecting change, and what does it mean for the next decade of science fiction? We reached out to a group of BIPOC editors and curators working in science fiction what to ask what kinds of changes they’re seeing in the field so far, and what they think and hope the next decade will hold as a result of the way authorship is changing.

[Ed. note: All quotes have been edited for concision and clarity.]

How are you seeing science fiction change right now?

Nivia Evans, Editor, Orbit/Redhook: What I’ve seen as we get a wider array of people in the field is the way traditional tropes or stories suddenly feel fresh and new as soon as they’re taken out of the expected places. Like, The Lesson by Cadwell Turnbull is a first-contact story, but it takes place in the Virgin Islands. Some of the beats are familiar — the encounter with the alien, and trying to understand what the world is — but you’re being taken to an island nation that’s long been forced to feel insignificant on the global scale, and now they’re the first place of alien contact, and they’re in the public eye. That to me feels exciting. It’s what you want to do in the genre overall. In science fiction or fantasy, we’re used to working with tropes. That’s what people really love. They love seeing the things they grew up with remixed and rehashed. And as soon as you add new voices and cultures, new perspectives, the things people may have been tired of feel original.

Photo: Restless Books

Ruoxi Chen, Associate Editor, TorDotCom Publishing: The question being asked in dystopic stories is no longer as simple as, “What if this thing that’s always happened to marginalized people happened to the people in power?” Science fiction is digging into other histories. We talk about science fiction as this genre that always looks to the future, but it’s very much a genre about history. So a more complicated and intense exploration of that history, which is also a story of our future, is what I see happening now, and what I want to see more of in the future. If the old canon was written by the empire, then the future of the genre is being crafted and shaped by the children and grandchildren of that empire, the people who were affected by those horrible histories. You can’t write science fiction in 2020 without looking that in the eye. Both the present and the future are as much about Edward Said as Philip K. Dick.

Christina Orlando, Books editor, Tor.com: I like weird shit! I like things that break traditional formats. I think speculative fiction is primed and ready to be really, really weird. I like post-textual stuff like epistolary novels, like This Is How You Lose the Time War, where you have extra-narrative information. I’m also really excited for podcasting. There’s lots and lots of cool stuff by marginalized voices happening in podcasting. When we’re talking about sci-fi, we can’t just talk about literature, because podcasting is narrative fiction that often gets left out of the conversation. And there’s a lot of cool stuff like, Jordan Cobb’s Janus Descending, a really beautiful podcast that’s sci-fi horror by a Black female creator. They’re doing so many cool things. I’m really excited to see where podcasting goes.

Diana M. Pho, Story Producer, Serial Box: With the rise of audiobooks came the rise of indie podcast production companies, which have really contributed to our understanding of sci-fi media. Technology is helping people who would have been considered hobbyists reach a level of production quality indistinguishable from professional houses. The interaction between creators and fandom was already pretty close in sci-fi. That’s always been one of its standout features. And we’re going to see the two sides merging more and more, resulting in even more interesting ways of interactive storytelling.

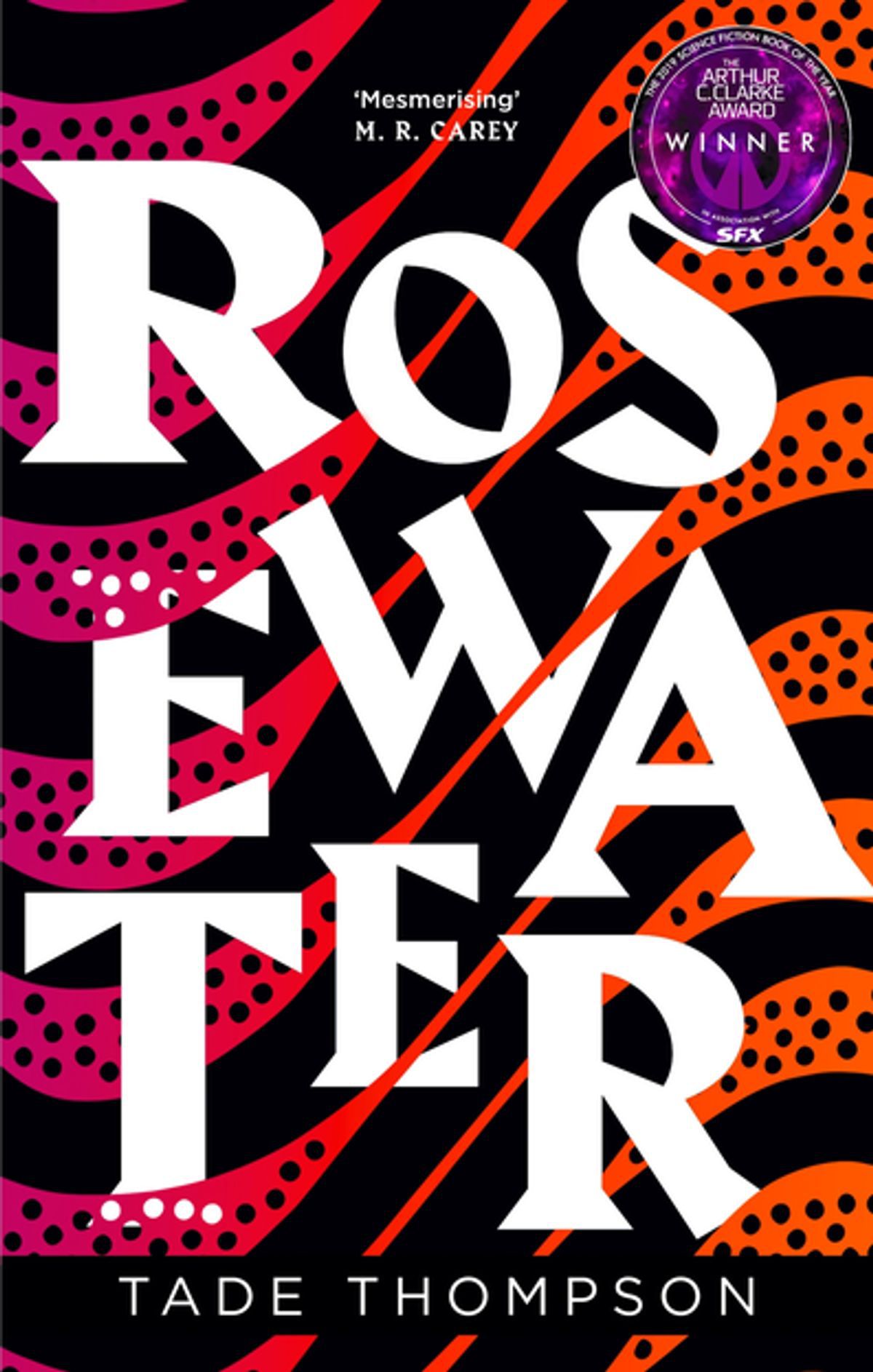

Nivia Evans: We all grew up with Western narrative perspectives, like, “This is how a story is told. This is how a plot develops.” But narrative structure is cultural. When you drill down into how stories are told across the Black diaspora, and what’s inherited from different places, you get fresh ways of looking at science fiction. Maybe it’s not always the traditional hero’s journey. Maybe things are broken down and reversed, or slightly out of order, with flashbacks or retrospectives, you’re piecing together narratives in different ways. MEM by Bethany C. Morrow does a really interesting thing with that, and Rosewater by Tade Thompson, another alien-contact story set in a town called Rosewater in Nigeria. They play with narrative structure and expectations. That can feel messy, but it also makes traditional stories feel fresh and original.

Diana M. Pho: Our understanding of science fiction has grown as it’s become part of pop culture. Even five years ago, I would have been hard-pressed to explain the butterfly effect in a time-travel story to most people. But now, because there’s so much science fiction entertainment in general, there is a more common understanding of what sci-fi means, and it has a broader reach than ever before. The intersection of science fiction culture and pop culture is going to change the next decade. There’s a collision course between what makes realistic fiction, genre fiction, and literary fiction. It’s all merging more and more. So we’re going to start seeing more books that would have been marketed as “genre” being marketed as commercial mainstream fiction, because people already get the concepts. You don’t have to explain anything.

Angeline Rodriguez, Associate Editor, Orbit Books: Readers have invested in infinite specific subgenres because of the curation of experience that’s been on the rise in all aspects of our lives. There’s this directed consumer experience that’s marketing something very specifically — you can go on Goodreads and look at the categories and say, “I want a science fiction novel, I want it to have spaceships, I want it to have hyperdrives, I want it to have an ensemble cast.” You can search by very narrow parameters, down to the tropes and the narrative experience. The nicheness and specificity of those categories has helped authors find readers who are looking for a very specific thing.

But a lot of publishers are struggling to figure out how to promote discovery, how to have a reader take a chance on a book they might not normally pick up. I think it’s increasingly important for sci-fi to reinvent itself, to try to introduce readers to something they might not know they’ll love.

Photo: MCD x FSG Originals

Ruoxi Chen: A lot of the most exciting work is being done not with books, but with short fiction. FIYAH magazine, Uncanny, Lightspeed — there are a bunch of amazing short-form publications. Sometimes the most fascinating stuff is happening in a thousand words, or five thousand, rather than at book length. Longer projects have emerged from those stories, but the barrier to entry is obviously smaller than getting a book contract, so there’s so much exciting work happening there. If you’re looking for the first breaths of something in the genre shifting, it’s in the short fiction.

Nivia Evans: There’s the fun side of science fiction. I think we all go into it for the adventure. But the way science fiction started, outside of the pew-pew, shoot-’em-up ray-guns aspect of it, is talking about culture and society. I understand the escapism of science fiction, but some of our best books, our classic science fiction, still had political messages. Dune at every point, especially in the later books, is working to tear down the ideas of oligarchy, of divine rulers, of corporations. What we get from reading Ray Bradbury and a lot of great authors like that is social commentary that uses science fiction to look at society as a whole, and take it apart and analyze it.

I don’t know if it’s because I am a person of color, but having authors of color deconstruct society and tie it to things that feel relevant to their lives gives these stories more impact. You’re automatically being pushed to think about the real world within the context of the narrative. To me, that is the best part about science fiction — taking this fun, enjoyable text and thinking, “How do we extrapolate this to our lives? Is it thinking about what space travel looks like? But then, if we’re all living in space, is it also looking at how women are treated?” You can extrapolate so many things out of science fiction.

Ruoxi Chen: So much classic science fiction presents these dazzling, inventive leaps about what the future could be, but against incredibly socially conservative backdrops. So the shift to inclusivity feels to me like it’s both a reaction to that old canon, and also something new. I was brought up on a lot of science fiction media that I still love, but if you watch Star Wars or Firefly or Blade Runner, those are visions of the future steeped in Asian aesthetics, Asian culture, and Asian mythology, but stripped of actual Asian people. You can love something that cuts you out, but that’s not the future of the genre that I want to see. So it feels reductive to say the new science fiction is “by us, for us,” but it is a true thing.

It really heartens me that there is enough space in the genre now where you can see, “This is Singaporean SF, this is Vietnamese SF, there’s Chinese SF, there’s SF from the Chinese diaspora.” So readers can say, “I’m interested in this specific reaction from this specific part of a given culture.” And authors can say, “We’re going to break out into a genre of a genre.” Ten years ago, [microgenres] were like, “Oh, are you into hard military sci-fi, or softer military sci-fi?” But now, there are so many little pathways and doorways you can go through, and these writers are all talking to each other.

What do you want to see more of over the next 10 years?

Priyanka Krishnan, Senior Editor, Orbit Books: I would like to see more imagination in experimenting with narrative structure and the methods of worldbuilding. Worldbuilding in SF/F is expansive, because the settings are often traveling spaceships or warring kingdoms or post-apocalyptic landscapes. But the texture of that worldbuilding lies in the small details, and those details are often very much informed, intentionally or unconsciously, by a writer’s own experience. So if part of what inclusivity means is for readers to be able to recognize themselves in the small details, then the best way to achieve that is to be publishing stories from a spectrum of voices, and all they can bring to the process of creating unique worlds, even when the basic touchpoints are familiar. I think we still have work to do on that front over the next 10 years. And it’s not something that’s specific to sci-fi, certainly!

Angeline Rodriguez: This is my bias coming through, but I would specifically love to see a return to form for Latinx speculative fiction. Some of the genre’s earliest origins, in magical realism and surrealism, had their most formative literary movements in Latin America already, with classic authors like Jorge Luis Borges, or Gabriel García Marquez, or Machado de Assis. I don’t necessarily want the Latin community to try to re-create those genres of bygone eras, so much as capture the spirit of that by once again becoming the standard-bearers of new ways of writing. I think we’re seeing the beginnings of this starting to happen with authors like Carmen Marie Machado, or Silvia Moreno-Garcia, or Mariana Enriquez, who are reinventing horror in a lot of different ways. I would love to see that happen in depth with science fiction.

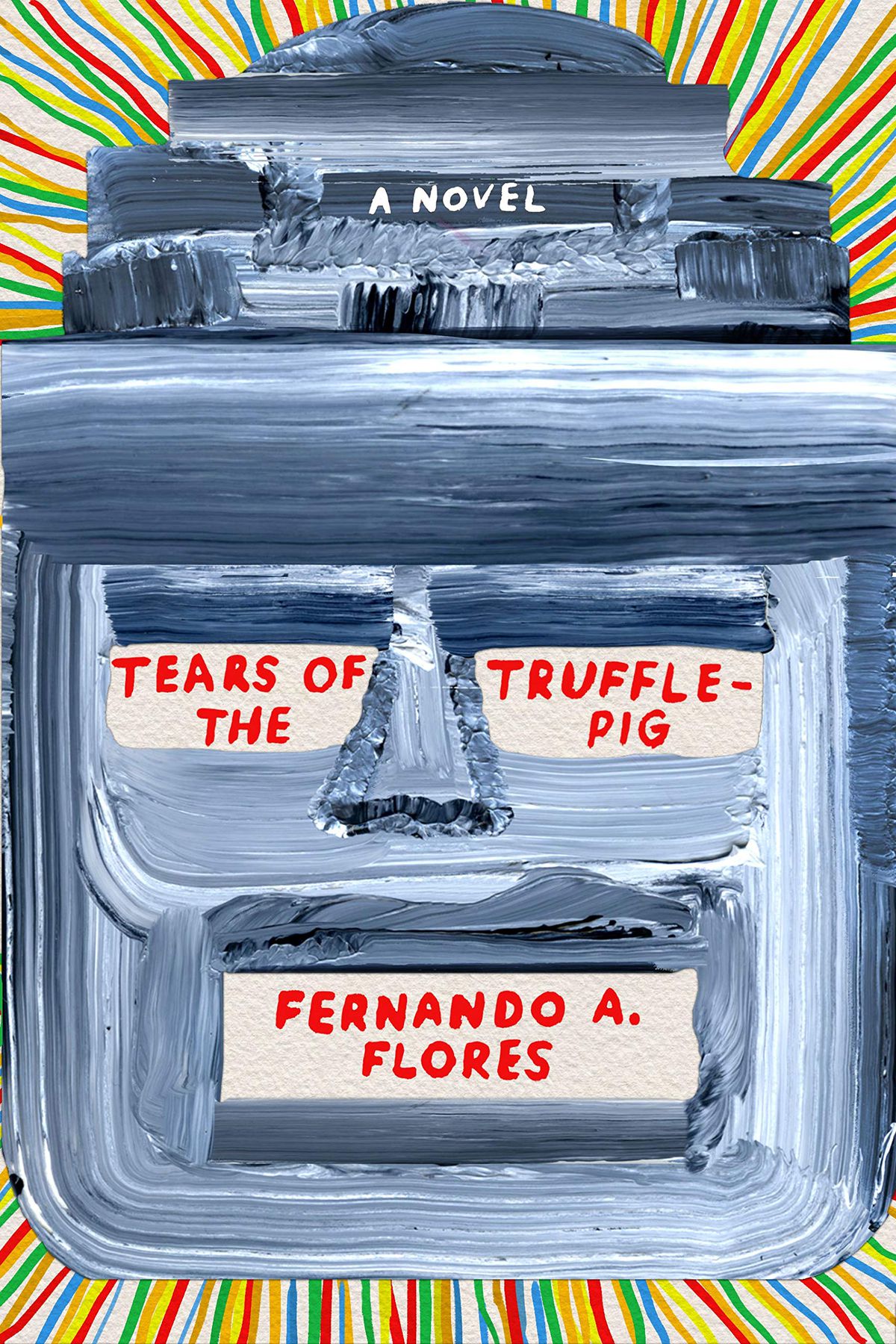

Fernando Flores is doing really interesting things with sci-fi about the Texas-Mexico border. He has a book called Tears of the Trufflepig that’s satirical sci-fi. There’s a Cuban author who goes by Yoss who’s recasting genre conventions, using space opera, to address colonialism in the Caribbean. So often with new writing from underrepresented authors, you see it pitched as, “You know, it’s Lord of the Rings, but diverse!” Or “It’s Dune, but it’s brown!” There are good reasons for doing it that way, based on how the industry operates. You’re often trying to re-create success. But I would like to see not, “This is the same old genre you love, but with extra melanin,” but new genres entirely, that are born from a non-white experience. Like they presuppose not-whiteness in their origins. I just really want genre to be centered from the margins, ultimately.

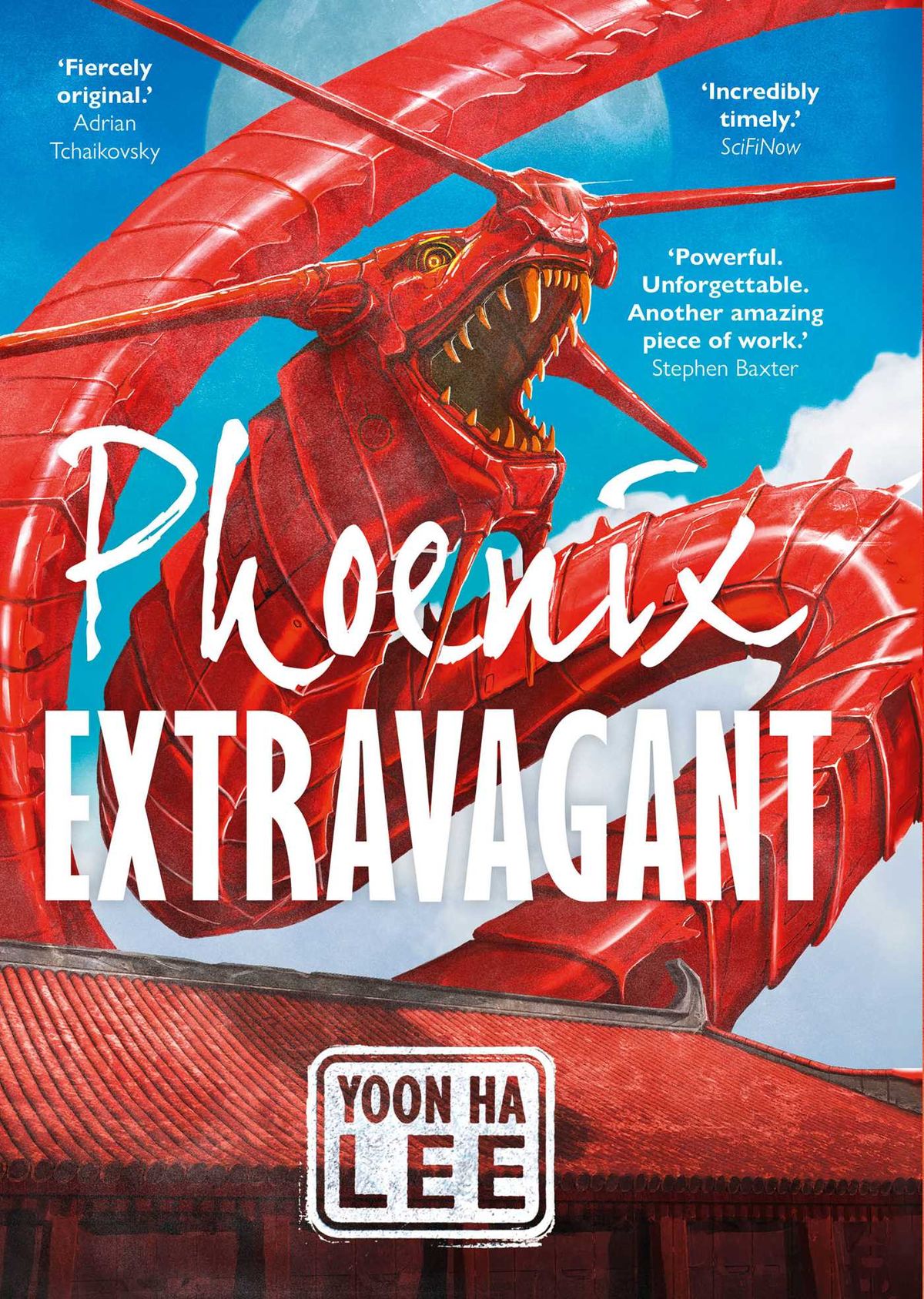

Christina Orlando: I’d really like to see more science fiction that reimagines systems that no longer serve us. That includes post-capitalist futures and post-carceral-state futures. I’d really like to see more fiction that toggles prison abolition and things like that, futures moving beyond capitalism, moving oppression. The trend toward hopepunk that we’re seeing right now is especially key for marginalized voices. I’ve seen a lot of queer writers tackling hopepunk futures, especially imagining queer-normative futures, like the one in Phoenix Extravagant by Yoon Ha Lee. Those are things I’m really excited about seeing.

I’m also really excited about publishers like FIYAH and smaller short-fiction publishers pushing the envelope and being really leaders in our field, and the Kickstarters that have popped up lately for speculative-fiction magazines coming from marginalized voices. I’m really excited to see where that takes us.

Priyanka Krishnan: Personally, I like stories that dare to be optimistic, and I would like to see a lot more of that across the board. Uplifting stories can actually be really helpful and healing for readers. It makes sci-fi a little different from fantasy, because fantasy usually takes place in a secondary world. There are parallels to our lives, but at the end of the day, you’re talking about secondary worlds and magic, whereas with science fiction, you’re talking about our possible futures. So lately, I’ve been moving away from darker, colder, dystopian reads, and wanting stories that dare to imagine how we get past these dark moments into a better future.

Angeline Rodriguez: I would like to see authors feeling less constrained by genre checkpoints. What a science fiction writer is can be up for interpretation and redefinition. In the earliest origins of the genre, greats like Ursula K. Le Guin and Octavia Butler oscillated between writing science fiction and fantasy with great facility. They blurred the lines between those two genres. And their science fiction contains many other disparate genres, like horror. They were able to experiment with genre in a way that as markets solidified and consistency of author brand became more important, we saw less of.

We’re seeing a renaissance of that percolating, with authors like N.K. Jemisin or Ann Leckie, who have published books in a variety of genres, and have reinvented science fiction so it more resembles epic fantasy, or writing fantasy that borrows the best parts of science fiction. They haven’t been as limited by genre walls. It would be really nice to see underrepresented authors — I just know there are so many people with just a wealth of wild ideas — reinvent those genre conventions.

Christina Orlando: So this may be my favorite thing that’s ever happened in my whole life: Oscar Isaac did an interview about how he didn’t fit in the seats in the Millennium Falcon, because they weren’t built for ethnic hips. We have a lot to talk about in science fiction about the future of body positivity, the future of non-white lead characters and non-white bodies being normalized. We’re talking a lot right now about character descriptions being racially charged, and how we can move away from that by normalizing ethnic features, and having machinery and spaceships built for non-white bodies, in ways that celebrate them. In the same way, we can talk about the trans experience being portrayed in futurism. I just want more people to look like me! It’ll be important in the future to have different types of characters, without demonizing the way we look.

Photo: Solaris

Diana M. Pho: All the big corporations are trying to break demand down into algorithms and individual pathways, to figure out what people want, and how they access them. Because of that, I think writers are being bolder and braver. Marginalized writers back been held back historically by feeling they had to figure out the game, like, what does it take to succeed if you are a person of color, if you’re queer, if you’re poor? How do you break into these circles that seem inaccessible to you? Some marginalized writers were thinking, “We’ve gotta build our own outlets, we’ve got to do it ourselves.” Others were trying to assimilate in order to get published. Over the next 10 years, I think the idea of assimilation in general will be broken down. Writers will be able to feel more open about writing based on their experiences, based on their communities, really tackling issues that they previously might have been afraid to talk about, in fear of sounding too niche.

Christina Orlando: We talk a lot about the X-Men problem, where there are sci-fi stand-ins for racism. We’re exploring racism or prejudice, but the victims are mutants or aliens or robots, or not human in some way. It’s implied that we’re talking about racism, but we don’t actually talk about race. Those are things I want to move away from. I think it’s an instinct for sci-fi writers to talk about the other in this way. But we need to talk about more sophisticated levels. What does it mean if someone is Latinx in space, and Mexico doesn’t exist? What does it mean to imagine our culture in that kind of future? I want to see us moving past the metaphors science fiction has been relying on for a really long time.

Diana M. Pho: People have already talked about diversity, inclusion, and representation as super-important. But linked to that idea is the concept of community and character-driven narratives, and the importance of specificity. Often in mainstream publishing, people talk about the concept of universality — your story has to be universal to reach the broadest audience possible in order to be a commercial success. Now, I think that sense of universality is being broken down in favor of specificity. Specificity will now be linked to what makes a universal story, as opposed to trying to encapsulate a broad, general idea of humanity.

Angeline Rodriguez: I would love to see sci-fi contend more with realism, which sounds paradoxical, but it’s really not. A lot of people think of sci-fi inherently as escapism or surrealism. But I think it’s a genre that can very much reflect our reality in a way that makes realist novels look like fantasy. If you’re escaping to a supposedly realist world, like, “I’m an Irish schoolgirl in love with my much more popular classmate,” these things also have their artifices and conventions. We need to come to terms with the fact that sci-fi is not inherently a non-realist category. In a lot of ways, it’s more equipped to reckon with our injustice in a way other genres aren’t. I would like to see more reckoning with colonialism, with colorism, with wealth inequality, with the power of the chauvinist governments. People outside the genre often want to assume it’s all just like spaceships and laser beams, but there’s usually something much closer to home powering that engine.

I think sci-fi is uniquely qualified to do that work, specifically, because it’s a counterfactual genre. It’s compelling you to imagine things not as they are. Obviously you can use that to imagine a better future, a utopic future, but you can also use it to imagine a world where the dystopic qualities of the real world are highlighted in a particular way that makes them easier to reckon with.

Priyanka Krishnan: There are a lot of authors coming out of China, and a lot of works in translation from there. I don’t know that India has matched up in terms of being a market to that level, but I don’t think that’s due to a lack of voices in this space. It’s definitely a place I would like to be tapping into more in terms of seeking out new voices, whether it’s works in translation, or not. There are a lot of really interesting things to explore for a writer coming out of India if you’re talking about the future. A lot of sci-fi is obviously based on current conditions, and whether you’re talking about climate change or population issues or class disparity, there’s a lot of subject matter to explore in India. I’m definitely seeing far fewer Indian sci-fi authors than I would like. I hope that’s something that will continue to change over the next 10 years.

Christina Orlando: Science fiction helps us imagine possibilities, but I struggle with that a lot. I don’t want to put that work on to writers. It’s not really their job to imagine better futures for humanity. I think speculative fiction, sci-fi writers especially, like doing that, but we shouldn’t be relying on writers to do that. That should be the job of people in charge, like politicians and world leaders.

I want to stay away from saying, “Fiction inspires people, and we want everyone to take up arms like Katniss Everdeen!” I think that’s really reductive. But I also think reading fiction that imagines better futures, where people see themselves represented and see possibilities reflected that they maybe never thought were possible, that does crack people open to question how they’re represented in the real world. It’s not about giving answers, but allowing for more questions.

Photo: Subterranean Press

Diana M. Pho: Reading creates empathy, and connected to empathy is curiosity. There’s so much sci-fi content because there are so many different types of stories, and people are always looking for something new. That’s a driving force for them to take a chance on stories by marginalized creators, stories outside their comfort zone, stories that take place in a setting they may not live in, or a society that may have not encountered before in real life, but will definitely read about in a book. I think people are looking for that sense of originality and newness.

Angeline Rodriguez: No matter where genre goes, there are hundreds and hundreds of sci-fi books published every year. The books people have loved, and continue to love, that might be a certain formula, or might be a certain type of person writing them that people don’t want to see change — those are still going to be published. The genre expanding to new audiences doesn’t mean there’s less of the pie for the existing audience. This is about making the pie bigger in general. Some people are always going to perceive diversity as “If you have something, I can’t have something,” which couldn’t be further from the truth. We’re trying to make the audience even bigger and more inclusive, and more adventurous.

To conclude each interview, we asked participants to recommend a few books that represent what they want to see in the future of science fiction.

Angeline Rodriguez: Fernando Flores’ Tears of the Trufflepig is Thomas Pynchon with a punk-rock sensibility, and a great example of what SF situated in the trap door between the real and unreal can do — it plays with the borders of genre constantly, taking place quite literally on an alternate-universe Texas-Mexico border where a third wall is being erected and a black market of extinct animals and indigenous pain flourishes. It’s a funhouse mirror of our headlines that gets to the crux of why they exist so much more effectively and cleverly than the latest “realistic” white-penned narco-thriller.

And I love Marissa Levien’s novel The World Gives Way because it takes the generation ship, which is such a classic SF setting, and grounds it so thoroughly in a day-to-day that looks and feels so much like our own, and is subject to its same hazards and heartbreaks, that it feels even stranger in a way than the far-future visions of Gene Wolfe or Arthur C. Clarke.

Nivia Evans: I mentioned Rosewater by Tade Thompson. It’s super-smart and ambitious, but also very grounded and accessible. One of my favorite books is Famous Men Who Never Lived, by K. Chess. It’s really fun. It has multi-dimensional travel, but it’s so character-focused and grounded. It’s the story of a person from a parallel dimension coming to ours as a refugee, and going on the hunt for their favorite science-fiction novelist, who was super-famous in their world, and never really took off in ours. I think that’s just a clever way of talking about lost culture and what it means to have to start new. Another of my favorite books recently is A Big Ship at the Edge of the Universe by Alex White. It’s all the joys of science fiction — a big ensemble cast on a quest.

Priyanka Krishnan: I love Becky Chambers, who wrote The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, A Closed and Common Orbit, and Record of a Spaceborne Few. They’re stories about character relationships, and how we take care of each other. There’s a lot about innovation, and aliens, and space adventures, but there’s just a warmth and compassion to her storytelling. Her Wayfarers series is about misfit crews, humans and aliens alike, having adventures on ships. It’s very familiar territory for SF readers, but there is such heart to her storytelling, and thoughtfulness in the way she creates her characters and explores their relationships. Her books are like a cozy sweater!

And C.A. Fletcher’s A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World is a wonderful post-apocalyptic story that manages to capture both the desolation and the beauty of traveling through the ruins of the world, and it features some very good dogs, none of whom are harmed, don’t worry. And I finally recently read All Systems Red, the first in the Murderbot Diaries series by Martha Wells, which I can only describe as delightful.

Christina Orlando: I have to shout out my man Tochi Onyebuchi. Riot Baby is the most spectacular thing I’ve read in a really long time. Ken Liu’s The Hidden Girl and Other Stories just blew my mind. I went bonkers for a solid three days reading that. It’s just so wild and exciting. It tackles a lot of big questions about the future of technology, and how we communicate, and keep relationships going over the internet. That’s really exciting to me. I mentioned Phoenix Extravagant by Yoon Ha Lee, which is a queer-normative future with mechs, which is always fuckin’ cool. There’s a lot of stuff coming out next year that I’m really excited about. S. Qiouyi Lu has a cyberpunk book coming out from Tor.com Publishing next year, which is called In the Watchful City. S is a spectacular, smart human being. So I’m very excited about that.

Ruoxi Chen: Tochi Onyebuchi’s Riot Baby was written in the wake of what’s been happening in America. He’s responding to Eric Garner, to Tamir Rice, to that entire history. Its main characters have superpowers, and it’s got elements of classic anime, Gundam Wing, and Akira, but all of that is rolled into how terrifying and amazing it is to be Black in America.

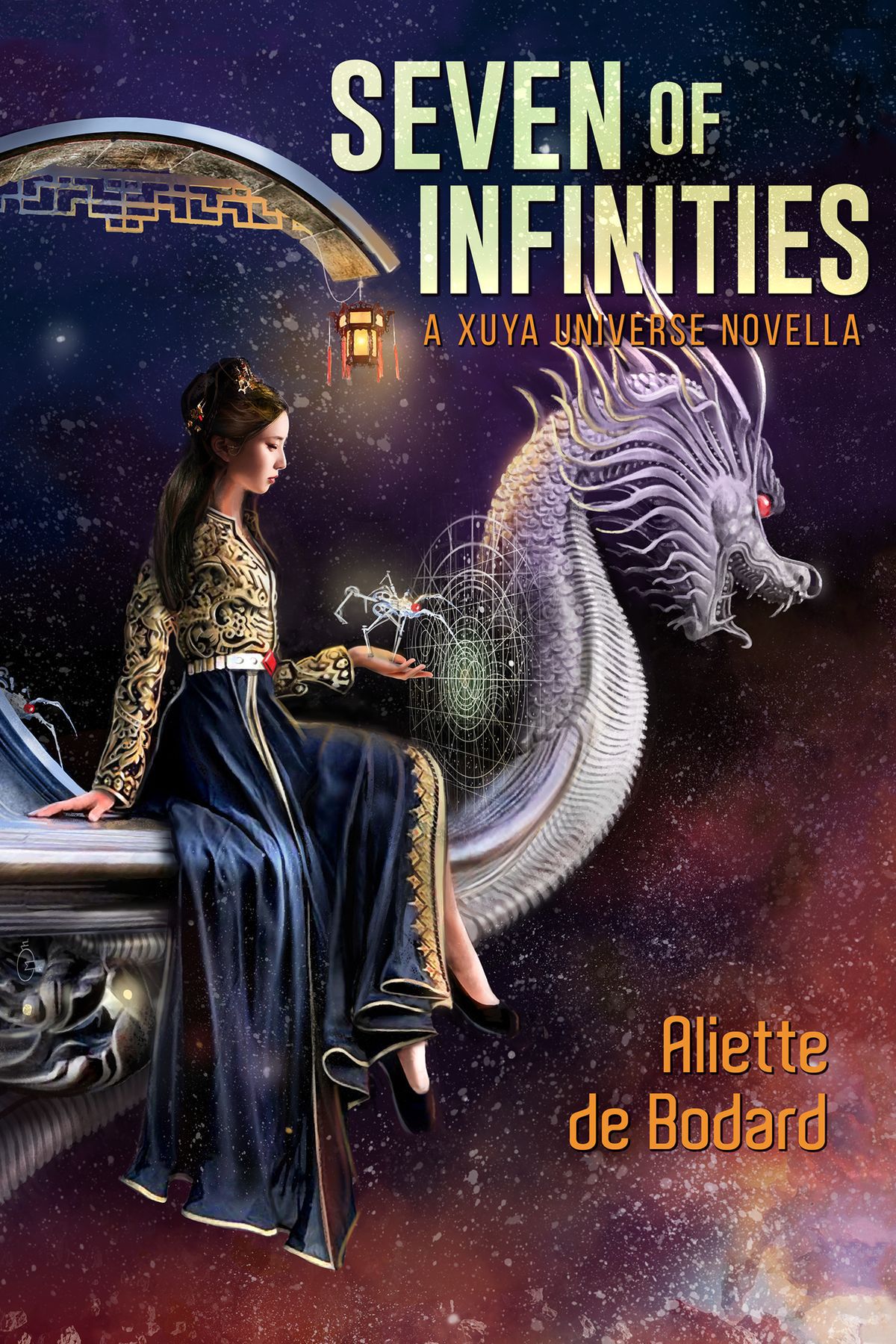

On the space-opera side, Aliette de Bodard, who has every award on planet Earth, and probably some other worlds, is doing incredible work with her Xuya universe, which is far-future space opera. But the originating premise is that China discovered the Americas before Europe did, and it kind of springs from there. So when I mentioned seeing Asian space opera and sci-fi created largely by white creators with almost zero Asian people in it, Aliette is writing what feels like an answer to that. She’s Vietnamese, and just to see her take on Sherlock Holmes and Watson as sentient spaceships, in the context of a Vietnamese-inspired space Empire, that’s incredible. But as far-future as it is, it’s rooted in history. So there’s a lot of fascinating work being done in that space. Maybe 20 years ago, it would have just been referred to as Asian science-fiction/fantasy in a really broad way. The most you could have hoped for is a progressive white writer who bothered to do some research. But now, you see the diaspora writing for themselves.

Diana M. Pho: Lettie Prell is a really wonderful short-fiction writer. All her stories explore transhumanism, and are based on the premise that the Singularity is not a one-time event, it will happen in different communities all across the world. So they’ll all have a different understanding of what it means to have a transhuman identity, to incorporate that into their communities in different ways. I really love that.

Vina Jie-Min Prasad is another short-fiction writer exploring science fiction in innovative ways, but with a really strong sense of fun. A lot of their stories have to do with robotics and the future, but also families and how they intersect, and how do you build new connections? And P. Djèlí Clark has mostly written in fantasy. He has a background as an academic historian, which really feeds into the type of stories that he tells, and the focus on not just having a really great, action-filled story with interesting characters, but also putting technology in context, which really pushes authors forward, and makes the ones that stand out, stand out.