The #DisneyMustPay viral campaign to get Alan Dean Foster paid faces murky legal waters

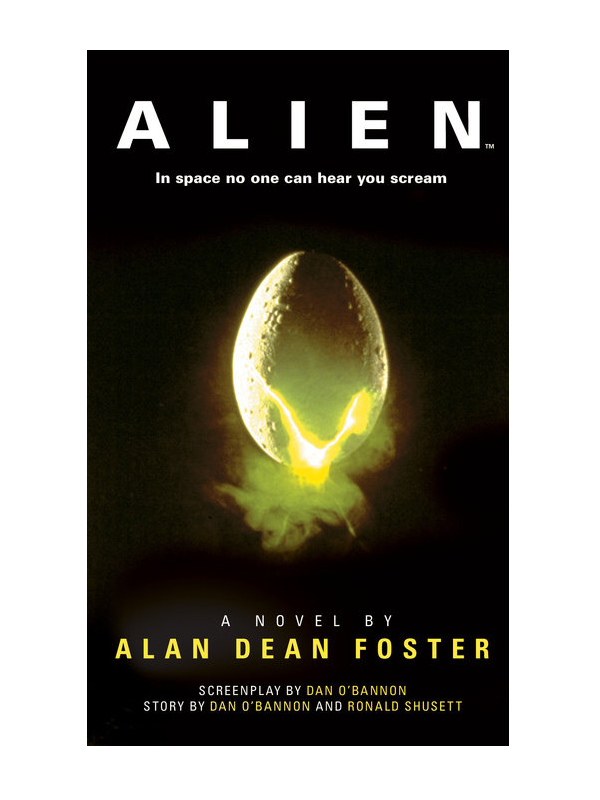

This November, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, a professional organization for genre authors, dropped a bombshell announcement that shook the science fiction community: For several years, author Alan Dean Foster had been trying, without success, to get paid for several major tie-in novels adapting movies from the Star Wars and Alien franchises. While Disney has kept the books in print with other publishers, with Titan handling Alien and Del Rey on Star Wars, Foster says he hasn’t received royalty payments for new editions. So, he had turned to SFWA for help, and the #DisneyMustPay hashtag was born.

According to SFWA, the incident sets troubling precedence for others in similar positions. If a publisher can get out of paying an author by having the license travel to another company, it could undermine the livelihoods of many writers who made their livings writing novelizations and tie-in novels for some of the biggest media franchises in existence. Moreover, since Foster and SFWA went public with their claim, other authors have spoken to Viaggio247 to say that they too haven’t been paid for work now owned by Disney after the acquisitions of Lucasfilm in 2014 and 20th Century Fox in 2019.

What I’ve learned from investigating the claims highlights the perilous position that writing for popular, existing properties poses for creators. The legal landscape is tilted towards the corporations — and the publishers under them — making the system tough to challenge.

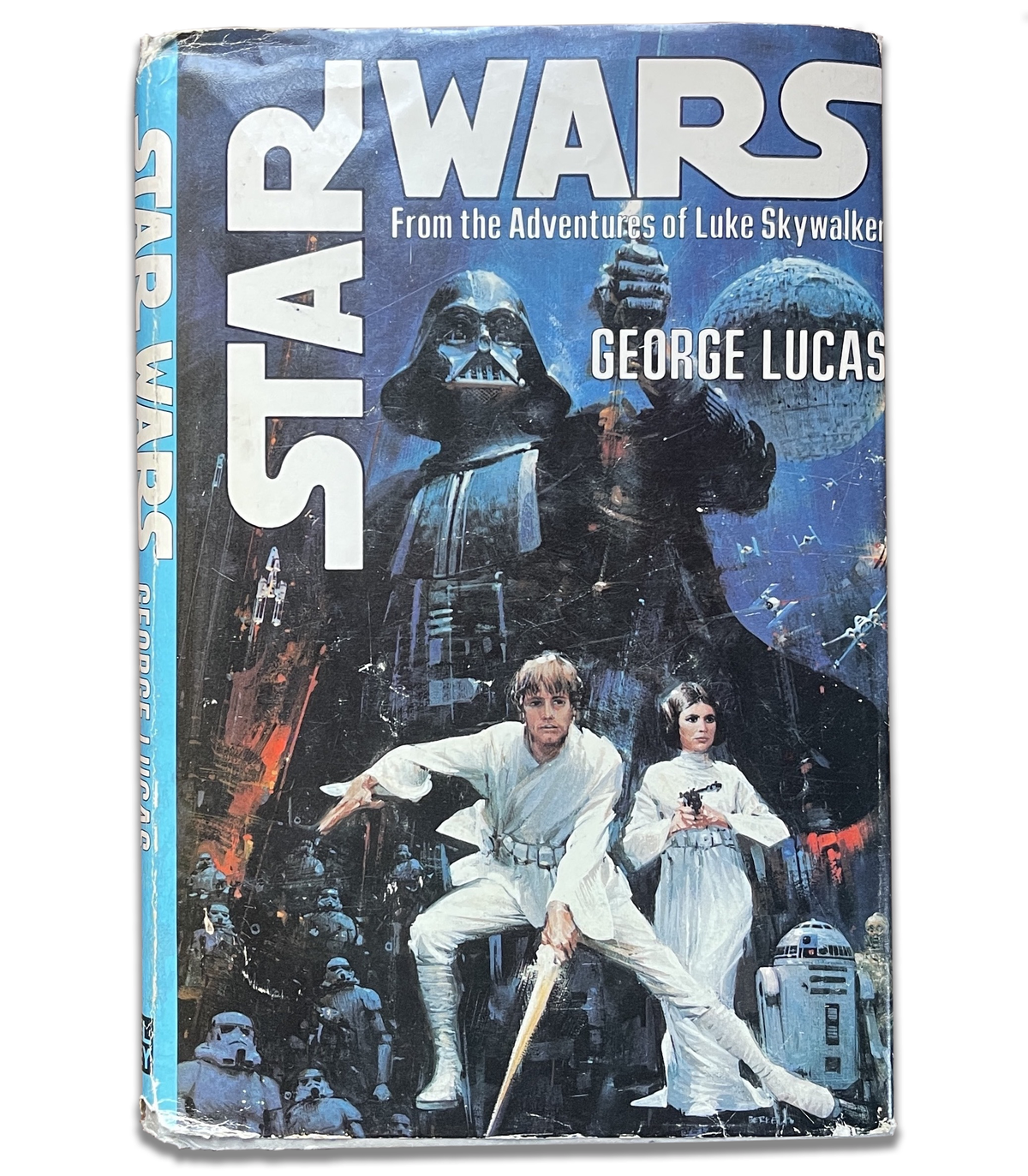

Photo: Andrew Liptak; book cover: Ballantine Books

On Nov. 12, 1976, a paperback novel called Star Wars, “written” by George Lucas, appeared on stands. With six months to go before the film would debut in theaters, Lucas’ company was hard at work licensing the property out to other companies that could produce shirts, toys, and comics that could promote the release. This included a pre-release novelization: Lucasfilm hired 29-year-old writer Alan Dean Foster to ghostwrite the book, as well as pen a sequel that could easily be spun into a second, lower-budget Star Wars film if the first underwhelmed at the box office. Foster had already been enjoying a career as a science fiction author, selling his first story to Analog Science Fiction and Fact in 1971, and his first novel, The Tar-Aiym Krang, a year later. Armed with Lucas’ script and concept art, he produced a 272-page book in just six weeks. When it hit stores courtesy of Ballantine Books in 1976, few realized who had actually written the novel.

Still, after the success of Star Wars, Foster found himself a go-to person for movie novelizations. Over the years, he’s penned dozens of novelizations for franchises like Aliens, Star Trek, Dark Star, The Black Hole, Clash of the Titans, Outland, The Thing, Krull, The Last Starfighter, Starman, The Chronicles of Riddick, and others. They were all written in addition to his own original novels.

The nature of a work-for-hire contract means an author who’s written a tie-in novel will have little control over where their story ends up; how characters, situations, or details are used after they turn in their manuscript; and even the copyright of the work itself. It’s a tradeoff: Foster might not own the book, but the product may provide a steady revenue stream for years, especially if the franchise is popular with audiences. Write enough of them, and those tributaries will feed a healthy river.

Shortly after Disney acquired 20th Century Fox last year, Foster says that his royalties for his Alien novels stopped coming. He and his agent first attempted to resolve the issue with the book’s publisher, Warner Books. According to Foster’s agent Vaughn Hansen, while Foster and the organization were working to uncover the provenance of those rights, it became clear there were also missing payments for his Star Wars novels.

Unable to resolve the issue directly, the pair took their complaint to SFWA’s Grievance Committee, a group within the organization that is designed to help authors who are having issues with their publishers. SFWA went to Titan Books, the publisher that currently publishes Foster’s Alien novels, and were told that they had to instead speak with the rightsholder: Disney. (Titan Books did not respond to comment for this story.) SFWA President Mary Robinette Kowal tells Viaggio247 that they attempted to resolve the situation by contacting the conglomerate, asking that the books be taken out of print until such time that payments to Foster resumed.

According to Kowal, Disney lawyers told SFWA that while it owned the underlying rights to Foster’s Alien novels, among others, holding the copyright did not obligate the company to pay him royalties — his contract was with Warner Books, not with 20th Century Fox or Disney. During SFWA’s November press conference, Kowal explained that the organization had trouble setting up a meeting with Disney to discuss and clarify the issue. Furthermore, Disney asked for their discussions to be kept confidential and that whatever they discussed couldn’t be used in further legal action. (Representatives for Disney declined to speak to Viaggio247 on the record for this story.)

An insistence on confidentiality frustrated SFWA committee hoping to help Foster. “What they have said is that they acquired the rights and not the obligations,” Kowal tells Viaggio247. “We feel fairly confident that if we can talk to someone from the publishing arm of Disney, that they will understand how these things are supposed to work. And that much of this is probably just something that has happened during the process of acquisition, but we can’t get past their legal branch, which is making this completely ridiculous argument.”

Disney’s argument: it wasn’t obligated to pay royalties or provide royalty statements for the Alien novels because Foster had signed a contract with the publisher, Warner Books. And because Disney now owns the copyright to each of the novels, it can redirect them to whatever publisher it deems fit. Those involved with SFWA believe that Disney’s interpretation of copyright law isn’t accurate and that there are still obligations that carry over with Foster’s contracts. The situation with Foster’s Star Wars novels, now published by Del Rey, are a bit murkier. Foster originally signed a contract (which Viaggio247 was able to review for this story) with the Star Wars Corporation, which guaranteed royalties for each book sold. The royalties continued when SWC became Lucasfilm in 1977. However, Foster, his agent, and SFWA say that they haven’t been paid since Disney acquired Lucasfilm.

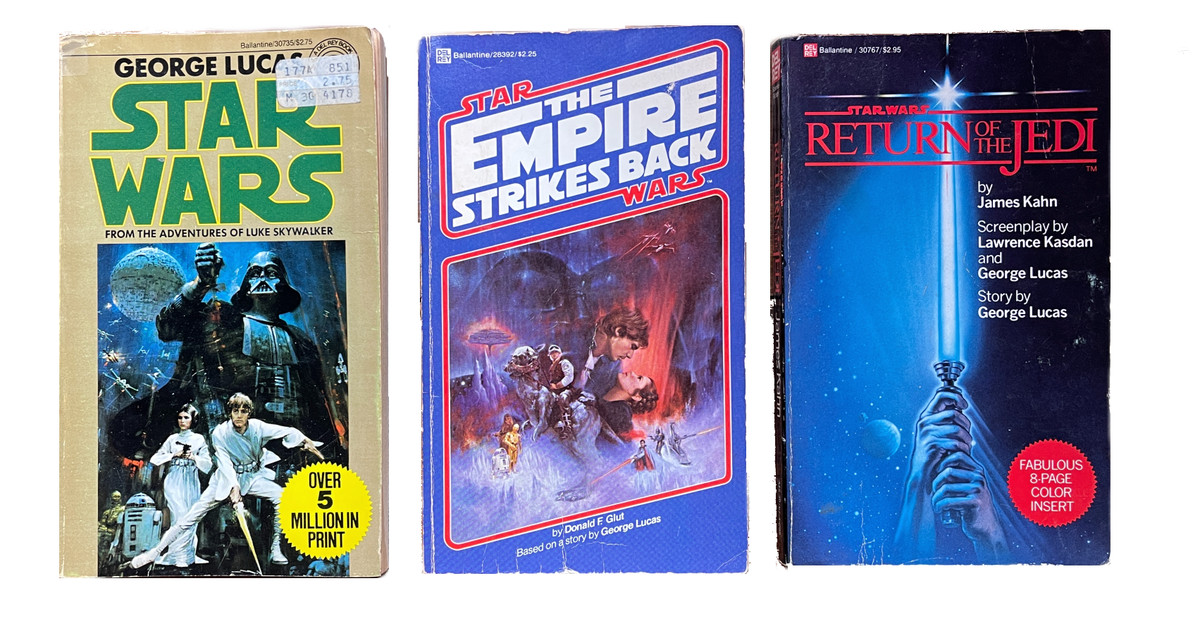

Photo: Andrew Liptak; book covers: Ballantine Books

Unpaid royalties appear to be an issue that affects other writers. Four additional authors have come forward to Viaggio247 to confirm that they haven’t been paid royalties for work now owned by Disney, for works that appear to have been transferred to other publishers: Rob MacGregor, who wrote the tie-in novel for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, as well as several additional tie-in novels; Donald Glut, author of the Empire Strikes Back novelization; James Kahn, author Return of the Jedi and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom novelizations; and Michael A. Stackpole, author of the X-Wing comics, Star Wars: Union, and Star Wars: Mara Jade — By the Emperor’s Hand. Without seeing contracts or the full details of the nature of the transfer of property from Lucasfilm to Disney, it’s hard to know if each author falls into the same situation as Foster, but the result appears to be the same: They haven’t received money that they feel entitled to for the work that they published.

In MacGregor’s case, he reported that a couple of years after Disney acquired Lucasfilm, his royalties stopped coming. After asking around at his publisher, he was told that “the license is no longer selling your Indiana Jones titles. As a result, there is no royalty bearing activity this statement period.”

Stackpole’s comics came out from one publisher, Dark Horse Comics, only to be later reprinted by another, Marvel. He notes to Viaggio247 that this situation doesn’t affect his prose novels like his X-Wing novels or I, Jedi — he’s still getting royalties for those from Del Rey. But he began to notice issues with his comics shortly after Disney transferred the Star Wars comics license away from Dark Horse Comics to Marvel Comics, which Disney already owned. After speaking with another writer who’d written for both Dark Horse and Marvel, Stackpole learned that the writer was getting royalties from reprints, but only because they were already in Marvel’s system prior to its acquisition by Disney in 2009. “It was his understanding that if you hadn’t worked for Marvel, if you weren’t already in their royalty system, you just weren’t,” he says. (Dark Horse Comics and Marvel didn’t respond to a request for comment by the time this piece was published.)

Photo: Andrew Liptak; book cover: Dark Horse Comics

Book royalties, Stackpole says, can be a complicated issue, and noted that the way one publisher conducts its business doesn’t necessarily carry over to another. His original contract for the X-Wing books didn’t provide a clause for ebook royalties, so the original publisher, Bantam Spectra, unilaterally issued a small royalty rate when the novels were published digitally. But because that clause wasn’t in his contract, Del Rey didn’t continue the practice when it acquired the license and began republishing the novels. Stackpole explained that he didn’t pursue the missing royalties because he figured it would be too small a sum and that he had other pressing issues in front of him. “You also have to keep in the back of your mind: Would raising an issue like that be something that would sour them on using you in the future?”

The concerns raise a question at the heart of the royalties issue: Is the fight worth it? “In principle, absolutely,” Stackpole adds. “We all want to be paid the money that we’re owed, but finding a practical solution or a legal remedy, it really is not economical either in time or money.”

Lawyers familiar with contract law tell Viaggio247 that Disney’s arguments, that the transfer of the property to another publisher, and the ending of an original publisher’s edition of a book, nullifies any obligation to pay a writer or establish a new contract, might hold up. Companies buy assets and not the liabilities all the time, precisely because they don’t want to shoulder the burden of those obligations.

A long trail of author royalties, however small, would be a logistical and bureaucratic commitment. If an author’s contract doesn’t specify that Disney is on the hook for royalties, but the publisher that they signed with, then the issue would seem straightforward. Furthermore, absent any specific prohibition about assigning rights under or to contracts with authors, a company may assign that contract to another without approval from said author. But SFWA says that it’s spoken with its own attorneys who uphold its interpretation of the situation. Kowal also notes, “There are plenty of things that are perfectly legal, but which are completely immoral.”

Image: Titan Books

Speaking to Viaggio247, Foster notes that while he’s heard of other authors in similar positions who haven’t come forward, he isn’t sure about the scope of the issue. That’s due in part to the isolated nature of the writing business. “We mostly get together to talk about these things,” he tells Viaggio247. “And this is not a general subject of conversation with writers at conventions we’ve had. What you do is you go to your agent, then your agency files again and again and again, calls again and again.” Sometimes, the problem also is hard to discover: his agent noted that when the royalty statements stopped coming, they were left blind, unable to account for how many copies were sold and thus what he might be owed. Now, whatever the legal case may be, SFWA is waging a public battle with Disney over what it sees as a moral imperative.

“For all I know, there are hundreds of writers in exactly the same situation,” Foster says. “We’ll figure it’s Disney, or this company or that company. And I can’t do anything about it, because I’m just me. And they don’t realize that they’re in a big boat with a lot of other people with the same situation until somebody steps forward and says ‘look, this has to stop, it’s wrong.’”

Foster’s works have continued relevance for the franchise. His novelization for A New Hope sees Luke Skywalker flying in Blue Squadron — rather than Red Squadron in the final film, a change between the works. In 2016, Blue Squadron finally got its moment to shine in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, seemingly a nod to the original screenplay. Other elements from Foster Star Wars published-but-never-formally-adapted sequel, Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, have appeared in prominent fashion in Disney’s revitalized franchise: the story is set on the planet Mimban, which was mentioned in the Clone Wars animated series, as well as Solo: A Star Wars Story in 2018. The Kaiburr crystal that was the focal point of the novel found new life in Rogue One and other parts of the franchise (now called Kyber Crystals.) With the recent announcement of a Rogue Squadron movie from Patty Jenkins, Stackpole stands to miss out on income from the various X-Wing comics that he wrote in the mid-1990s, and which are now being published by Marvel Comics. With Disney’s takeover and absent royalty statements, Foster isn’t even sure what money he might have otherwise earned in the last couple of years.

As Stackpole points out, there would be significant and expensive barriers for him and SFWA to embark on a legal pathway, and based on lawyers we spoke to for this story, it’s unclear how fruitful such a pathway would be. Ultimately, going public with SFWA to try and point out inequality might be enough to push Disney and its publishing partners into finding a way to quickly settle the case, either by paying the authors for their work, or having them sign new contracts with the new publishers.

What Foster has exposed by coming forward is a larger, systemic issue: Individual creators who’ve either made their living (or supplementing a writing career) by writing in existing worlds, and whose existences hang on the sharp edge of a knife, subject to the whims of corporate synergies, acquisitions or sales. The legal framework that these tie-in authors work within is tilted in the favor of the IP owners and publishers. A worst-case scenario for SFWA and its authors could occur if Disney opted to pull its various book licenses from its established, long-term publishing partners at the end of its current agreement and to a new publisher that might not be obligated to adhere to the original contracts from hundreds of authors. As the owner of the copyrights to all of those books, Disney likely has the legal ability to do so.

Stackpole echoes Foster’s observation about needing strength in numbers, noting that the entertainment industry does have existing remedies to help level the playing field: “The contracts for how actors and writers are paid when they work in movies or TV shows, are very strongly bent that way. But you have the Screen Actor’s Guild and the writer’s unions that have secured those rights. Those of us who are authors have not.”

For its part, Kowal says that SFWA has been working with other trade groups and IP holders to set up some industry best-practices. “The goal of the task force,” she told Viaggio247, “is to establish best practices so that when writers are faced with a situation like this, collective organizations can back this so that they don’t face them alone, and so that we can protect the group of writers.”

Solving the problem with a public relations campaign might put enough pressure on Disney for now, but ultimately, ensuring that authors aren’t cut out of the equation may require even greater action. Stackpole says that petitioning Congress to advocate for stronger copyright protections for creators and authors could level the playing field. “Congress often changes aspects of copyright to benefit creators, like the Disney corporation,” he says. “It is within the power of Congress to prohibit severing of contractual obligations in cases of copyright, which would solve a host of issues in the age of corporate publishing and the creation of branded intellectual properties.”