The 1972 population-anxiety movie Z.P.G. shows why

What happens to a dystopia that never comes to be? Does a story’s inaccuracy in predicting the future make it kitsch, a curio with no value beyond historic curiosity? Is an unrealized world the science fiction equivalent of a doomsday prophet after doomsday comes and goes? Or is there still something to be gleaned from a dark vision that might have gotten some particulars spectacularly wrong, but still taps into a broader understanding of how the future might go awry, and suggests what we might do to keep that from happening?

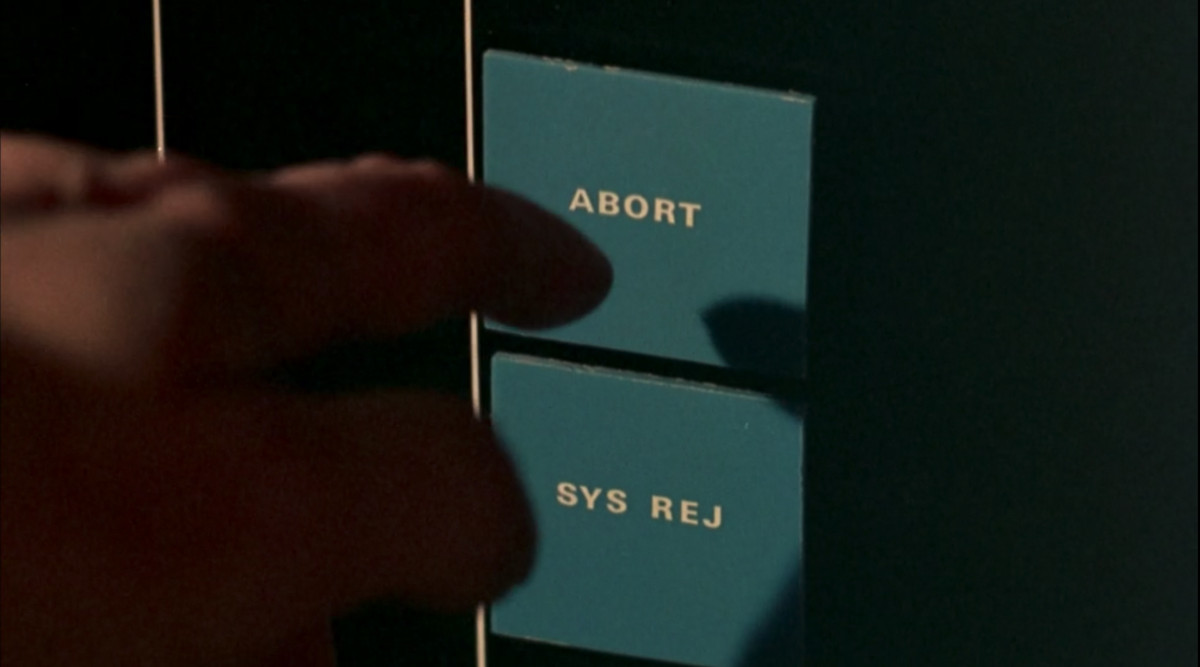

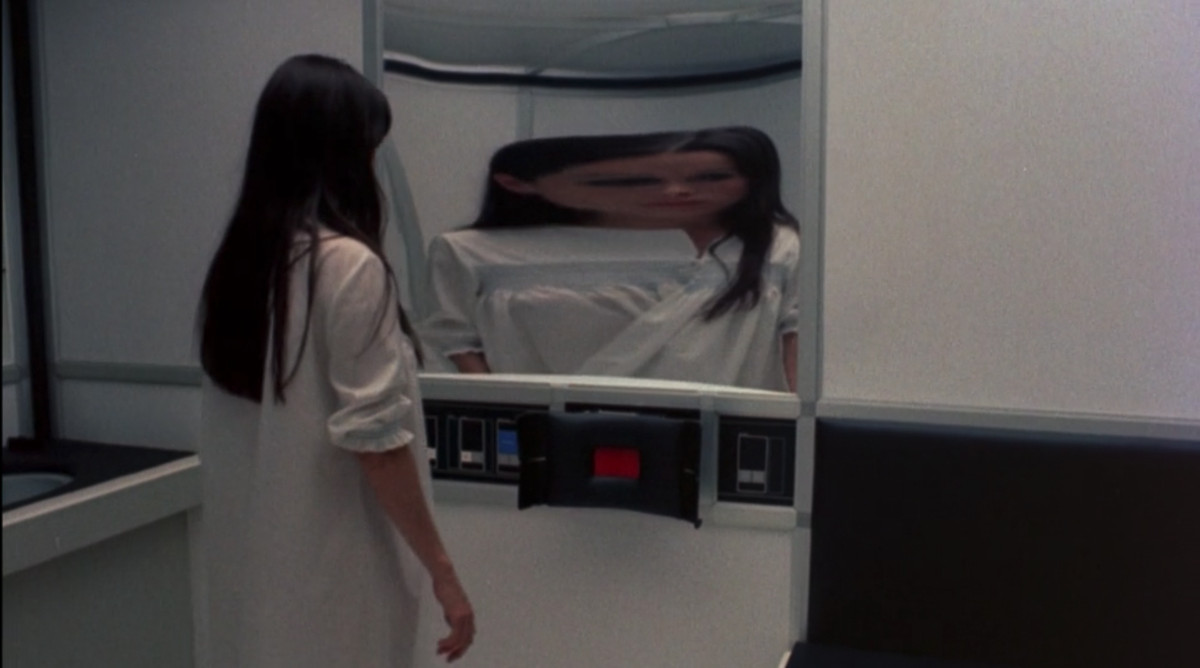

The 1972 science fiction film Z.P.G.: Zero Population Growth imagines a world destined to die not by fire, but by overcrowding. Set sometime in the early years of the 21st century, it takes place in a world undone by a population explosion, a development that has led to skies choked with smog and the mass extinction of virtually every animal and plant species. Those disasters have led the World Federation Council to impose a 30-year ban on childbirth. The WFC enforces its edict strictly but reluctantly, seeing it as the only hope for Earth’s survival. Sure, it might suck to force citizens to submit themselves to mandatory abortion machines after intercourse, and to be forced to use domed “execution chambers” to dispense with anyone who has a baby — a crime that means death for both parents and their illegal child. But what else can you do?

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

Science fiction has a long history of imagining too-crowded futures. Novels like Robert Bloch’s This Crowded Earth and John Brunner’ Stand on Zanzibar helped provide inspiration for films from Logan’s Run to Neil Blomkamp’s 2013 film Elysium. But few of the overcrowding-fears films are as deeply rooted in a specific time and place as Z.P.G. The film takes its name from the Zero Population Growth movement of the 1960s, which saw a solution to environmental and social ills in holding the population steady — and dire consequences if humanity followed its path of higher birth rates and longer life spans. The movement’s key texts included the 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb, written by Stanford biology professor Paul R. Ehrlich and his wife Anne Ehrlich (though the latter was initially uncredited). Its thesis is simple and scary: The Ehrlichs felt the human population was growing at a rate that would rapidly exhaust the planet’s resources, particularly its food supply. Here’s the opening passage:

The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.

That would be scary to read as the dread 1970s loomed just over the horizon. And anyone wondering what the aftermath of such a catastrophe would look like needed only to wait a few years to watch Z.P.G., and take in its vision of a world where society as we know it ceased to exist not long after the Nixon administration.

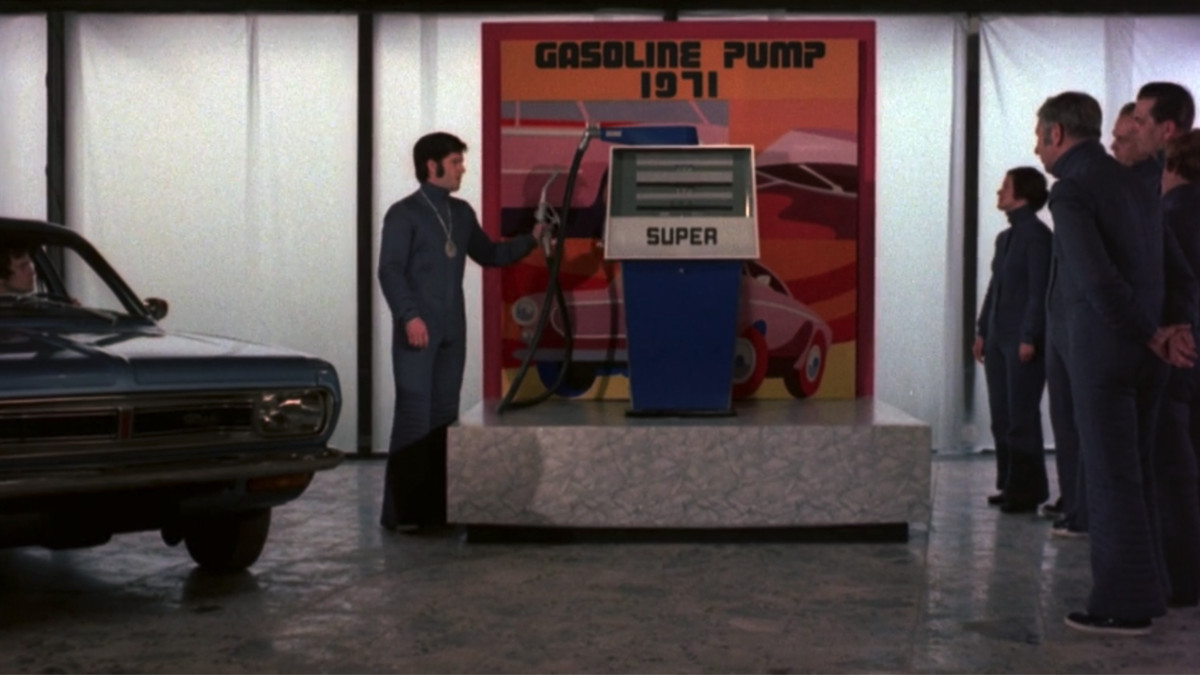

For Z.P.G. characters wanting to revisit the old ways, however, there was always the museum. In one of the film’s most striking sequences, married protagonists Carol (Geraldine Chaplin) and Russ McNeil (Oliver Reed) visit a museum dedicated to 20th-century life in all its excesses. There, they can simulate pumping gas into a car, peer through glass at exhibits dedicated to extinct animals like cats and dogs, and appreciate the lush greenery of rare plants. (The WFC may not have literally taken all the trees and put ’em in a tree museum, but it probably would have viewed Joni Mitchell as prophetic.)

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

Z.P.G.’s history museum is designed to educate visitors as much as delight them. It’s narrated by an unseen guide calling attention to the past century’s excesses and foolishness, and prominently featuring a “Gallery of Criminals” responsible for the world’s sorry state, including factories, airlines, and the Pope. Even the fun isn’t that fun: Russ and Carol get a shot at play-acting a typical 20th-century dinner party, the sort of gathering in which couples ate real food instead of nutritious paste, eaten out of tubes labeled with pictures of food that no longer exists. But that dinner quickly devolves into glum soap operatics.

Though Russ and Carol have waited a long time to score their museum visit, it leaves them unsatisfied. Their world is filled with depressing substitutes for the comforts of 20th-century life. People who want children have to make do with a visit to Babyland, where they’re issued mechanical babies to fill their need to nurture. (Shades of Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence.) “They’re all designed to be either playful or cranky!”, a cheerful salesman explains to the would-be parents waiting in line. The faux kids are also programmed to experience “the whole range of childhood diseases,” all the better to keep mom and dad busy. (Particularly since it’s unclear what, if anything, the WFC’s citizens do for a living.) But like the nutrient paste, the babies are poor substitutes for the real thing.

So poor, in fact, that Carol risks doom by skipping the mandatory abortion after having sex with Russ. Though he’s wary when she tells him, Russ becomes a co-conspirator, hiding his wife, and later, their child, then doing whatever he can do to keep them secret and safe, even entering into an increasingly risky power-sharing agreement with their best friends George (Don Gordon) and Edna (Diane Cilento), who take a liking to their baby that turns covetous over time.

Shot in Copenhagen with a largely British cast by American director Michael Campus (best known today for his next film, The Mack), Z.P.G. plays like a warning extrapolated from the headlines of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and from the Ehrlichs’ dourest predictions. And while the years that followed proved we were right to be worried about environmental issues, government overreach, and a booming population in general, it gets little right about the particular points that should have concerned its contemporary audience. It also found little purchase with filmgoers at the time, fading quickly at the box office to the accompaniment of poor reviews. (“Z.P.G.: A Big Zero For Effort,” chided a headline in the Philadelphia Daily News.)

So what’s to be taken away from a relatively obscure flop easily overshadowed by Soylent Green, a more memorable exploration of similar themes, released the year after Z.P.G.? Quite a lot, actually. Like George Lucas’ THX-1138, Z.P.G. provides a window into its era’s ideas of what dystopias would look like, complete with loose, unflattering jumpsuits, corridors bathed in fluorescent light, and pod-like living spaces. And though hampered at times by a limited budget, the film’s inventive miniatures and distinctive production design (including those creepy artificial babies) still look like a nightmarish vision of sterility and despair.

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

Even more nightmarish: the sense that the government actually is acting out of necessity, that the planet will have no future if it isn’t ruled with an iron fist. The WFC leadership isn’t enacting dreadful policies out of a lust for power, or to guard against some foreign enemy, but because oblivion awaits humanity if it surrenders control of even the most minute aspects of everyday life. The WFC is oppressive, but it might also be doing the right thing — the film offers no alternative to its brutality. Even Z.P.G.’s happy-ish ending offers no real sense of escape. It’s the sort of flawed film that lingers in the memory in spite of its awkward touches. (And, sure, sometimes because of them.)

As art and artifact, Z.P.G. has value in its fatalism, and the unremitting gloominess of its atmosphere and performances lends it value. (You don’t hire Oliver Reed to lighten up a movie.) If we imagine dystopias partly to serve as klaxons against what might be — in some cases, because of practices already in progress — it helps to see just how dire a future we might be building. Its depiction of a dystopia born of necessity is also useful — it’s a cautionary tale where past decisions have cornered humanity in a way where even injustice looks justified. Even where Z.P.G. gets the details of our future wrong, it’s still a depiction of a future we should work as hard as possible to avoid, in whatever ways we can.

Z.P.G. is also made remarkable by its ordinariness — it’s just one outgrowth of a type of thinking that remains with us in other ways. The Ehrlichs’ book and theories were everywhere in the 1970s. The idea of controlling the population by keeping people from having more children than they need to replace themselves is easy to understand, and easy to disseminate. (Never mind that the Ehrlichs also floated the idea of lacing the water supply with sterilants to control the population.) Paul Ehrlich became something of a celebrity for a while, a frequent talk-show guest and a particular favorite of Tonight Show host Johnny Carson, who had him on the show dozens of times, to talk about The Population Bomb and subsequent books like The Race Bomb, which prompted a frank discussion about the scientific absurdity of racism. But Ehrlich also gained attention for his 1979 book The Golden Door: International Migration, Mexico, and the United States (co-authored by Anne Ehrlich and Loy Bilderback), which warns of a new threat to American stability: Mexican immigrants.

Hearing Carson and Ehrlich talk worriedly about immigration, as Ehrlich calls for a “national debate on this entire issue,” means hearing a cultural institution normalizing the idea that America is running out of room, and English-speaking citizens enjoying a comfortable life will soon be crowded out by outsiders who don’t speak our language. In newspaper interviews, Paul Ehrlich blamed the United States for exploiting poor Mexican labor, emphasizing that undocumented immigrants were not exploiting government benefits. But in a 1979 Fort-Worth Star Tribune profile, he also warned that, “With the growing power of the Chicano population, you already see the groundwork of strife between Anglo-Americans and the 20 million Hispanics already in this country.” For the Ehrlichs, issues of environmentalism, overpopulation, and immigration became tangled up together in one big knot, to the point where they offered advice both to the Sierra Club and the Federation for American Immigration Reform.

Photo: Paramount Pictures via Viaggio247

While that group’s name was designed to be reduced to the acronym FAIR, the Federation for American Immigration Reform was and is a designated hate group driven by the ideas of John Tanton, a Michigan-based ophthalmologist. Its respectable-looking front hasn’t always been enough to hide ties to groups supporting eugenics, or private warnings that “for European-American society and culture to persist requires a European-American majority, and a clear one at that.” Tanton died in 2019, but not before seeing his ideas find fertile ground in the Trump administration.

Sometimes science fiction’s cul-de-sacs hide the seeds to other dark possibilities. The Population Bomb and its ilk raised some legitimate concerns, but the Ehrlichs’ work also inspired and encouraged hysterical responses, Z.P.G. among them. It now looks like a dystopian non-starter, inspired by ways of thinking grounded in predictions with fortune-cookie-like accuracy. But those ways of thinking didn’t so much disappear as mutate. Yesterday’s worries of overcrowding, like today’s concern about border issues, sometimes provide cover for bigoted and bad-faith arguments. We ignore dead dystopias at our peril. They have a way of shambling back to life in new forms.